Transit Center District Sub-Area Plan

INTRODUCTION

The Transit Center District Plan builds on the City’s renowned Downtown Plan that envisioned the area around the former Transbay Terminal as the heart of the new downtown. Twenty-five years after adoption of the Downtown Plan, in 1985, this part of the city is poised to become just that. The removal of the Embarcadero Freeway, along with the adoption of plans for the Transbay Redevelopment Area and Rincon Hill, has allowed the transformation of the southern side of the downtown in the cohesive way envisioned in the Downtown Plan. Projected to serve approximately 20 million users annually, the new Transbay Transit Center will be an intense hub of activity at the center of the neighborhood.

This sub-area Plan seeks to enhance the precepts of the Downtown Plan, to build on its established patterns of land use, urban form, public space, and circulation, and to make adjustments based on today’s understanding of the future. The Plan presents planning policies and controls for land use, urban form, and building design of private properties and properties owned or to be owned by the Transbay Joint Powers Authority around the Transbay Transit Center, and for improvement and management of the District’s public realm and circulation system of streets, plazas, and parks. To help ensure that the Transbay Transit Center and other public amenities and infrastructure needed in the area are built, the Plan also recommends mechanisms for directing necessary funding from increases in development opportunity to these purposes.

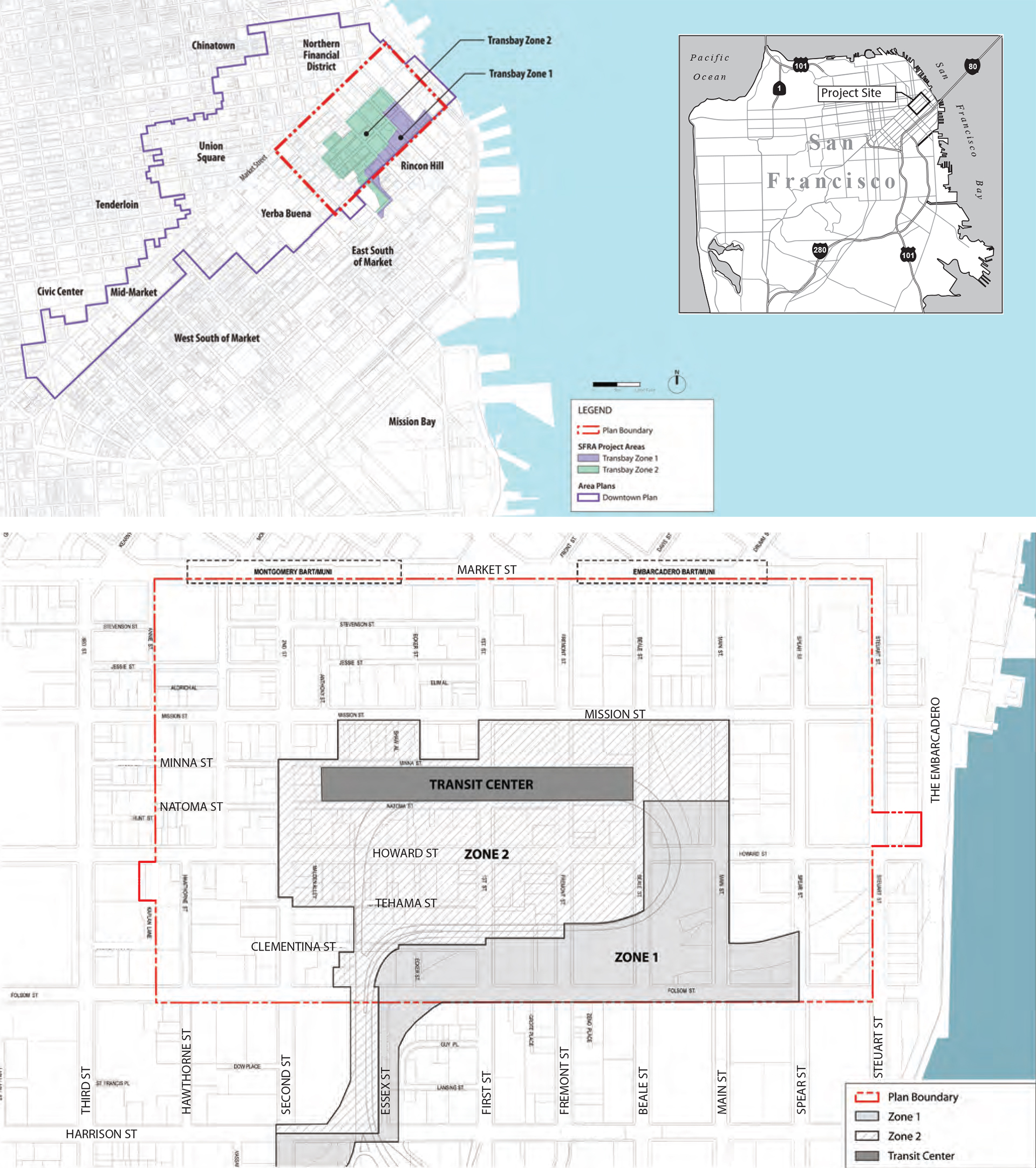

Plan Area Boundary

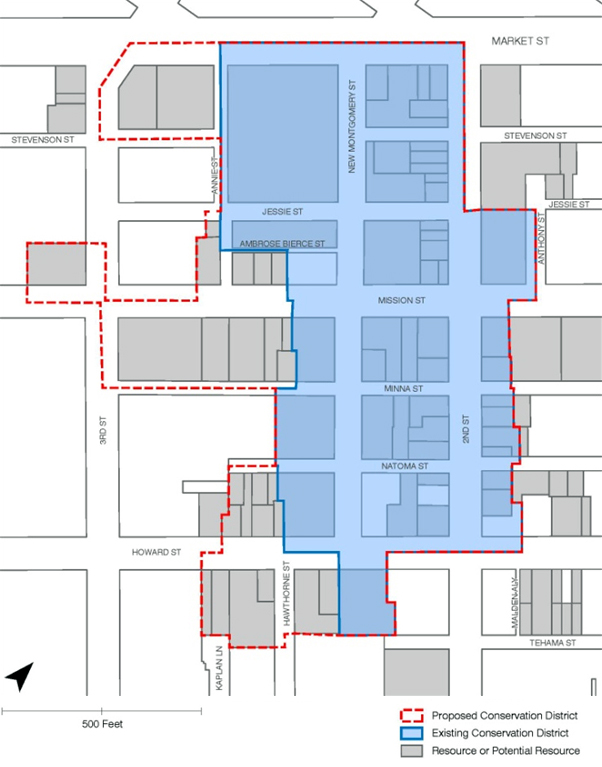

The Transit Center District, or Plan Area, consists of approximately 145 acres centered on the Transbay Transit Center, situated between the Northern Financial District, Rincon Hill, Yerba Buena Center and the Bay. The boundaries of the District are roughly Market Street on the north, Embarcadero on the east, Folsom Street on the south, and Hawthorne Street to the west. While these boundaries overlap with those of the Transbay Redevelopment Project Area, this Plan does not affect the adopted land use or development controls for Zone 1 of the Redevelopment Area and is consistent with the overall goals of the Transbay Redevelopment Plan.

The majority of the land within the Plan Area is privately-owned with the notable exceptions of parcels owned by the Transbay Joint Powers Authority (TJPA), of which at least two will be available for significant new development: the site of the proposed Transit Tower (in front of the Transit Center along Mission Street), and a lot (Parcel “F”) on the north side of Howard between First and Second streets formerly housed bus ramps to be rebuilt on adjacent parcels just to the west. (Additionally, Zone 1 of the Redevelopment Area, also within the Plan Area, is primarily comprised of publicly-owned parcels subject to the controls of the Redevelopment Plan as opposed to the Planning Code.)

Plan Goals

The overarching premise of the Transit Center District Plan is to continue the concentration of additional growth where it is most responsible and productive to do so—in proximity to San Francisco’s greatest concentration of public transit service. The increase in development, in turn, will provide additional revenue for the Transit Center project and for the necessary improvements and infrastructure in the District.

Increasing development around downtown San Francisco’s rich transit system and increased revenues for public projects are core goals of the Plan, but it is also critical that these policies be shaped by the values and principles of place-making that are essential to maintaining and creating what makes San Francisco a livable and unique city. The guiding principal behind the policies of the Transit Center District Plan is to balance increased density with the quality of place considerations that define the downtown and the city. With that in mind, the Plan is concerned with:

-

The livability of public spaces; ensuring sunlight, sufficient green space, accessibility, and attention to building details.

-

Scale of the built environment and the perception and comfort of the pedestrian.

-

The essential qualities and relationships of the built city at the macro level of skyline and natural setting, and the images that inspire residents and visitors everyday and connect them to this place.

-

The ground plane; a graceful means for moving from place to place, for pausing, for socializing, and for conducting business.

-

A comprehensive program of sustainability that goes beyond the basic underpinnings of land use and transportation, and includes supporting systems, such as water and power.

-

A transportation system that supports and reinforces sustainable growth and the District’s livability, one that ensures sufficient and appropriate capacity, infrastructure, and resources.

Plan Overview and Context

In 1985, the City adopted the landmark Downtown Plan, which sought to shape the downtown by shifting growth to desired locations. The plan sought to expand the job core, then concentrated north of Market Street, to south of Market Street, especially around the Transbay Terminal. The Terminal area was designated as desirable for growth for a number of reasons. First, the expansion of downtown south of Market Street would better center job growth on the major local and regional transit infrastructure along the Market Street corridor. Second, re-directing growth potential would protect important, valued downtown historic buildings from demolition. As an incentive, the Downtown Plan permitted development rights to be transferred from these buildings to the Transit Center District.

The Downtown Plan also emphasized the tangible and intangible qualities essential to keeping San Francisco a special place. The plan made broad, but well-articulated, gestures to preserve the best of the past, shape new buildings at an appropriate scale, and provide for a range of public amenities. Additionally, the plan included measures to ensure that the necessary support structure paralleled new development, through requirements and fees for open space, affordable housing, and transit, as well as a system to meter and monitor growth over time.

It has been 25 years since the adoption of the Downtown Plan and the time has come to revisit its policies and identify those that may need adjusting or strengthening. Downtown as currently envisioned by the Downtown Plan is at a point where it is largely built out, and the areas for growth are diminishing and limited. Furthermore, when the Downtown Plan was adopted, certain major pieces of infrastructure and facilities were in place or envisioned. Now, key changes have occurred and new investments are planned.

After being damaged by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the Embarcadero Freeway was torn down and the city was reconnected to its waterfront with a beautiful promenade, roadway and light rail line. This change enabled the downtown to grow southward, linking downtown to a future high-density residential neighborhood. The creation of this neighborhood was codified by the Rincon Hill Plan and the Transbay Redevelopment Plan, both adopted in 2005. Together, these plans guide the creation of a new residential neighborhood centered on Folsom Street, with a mixture of high, mid, and low-rise buildings. The high-rise elements add a new component to the skyline, creating a southern punctuation to the downtown.

During the Transbay and Rincon Hill planning processes, planners and decision-makers recognized the need to think anew about the downtown core. The Redevelopment Plan notes that the area north of the former freeway parcels along Folsom Street should be regarded as part of downtown and addressed in that context. This portion of the Redevelopment Area has been designated “Zone 2,” with jurisdiction for planning and permitting delegated back to the Planning Department.

By far, the most significant project planned for the District is the new Transbay Transit Center. Being built by the Transbay Joint Powers Authority, with construction commenced in 2010, this facility will replace the obsolete terminal with a 21st Century multi-modal transit facility meeting contemporary standards and future transit needs. The Transit Center will not only have expanded bus facilities, but will include a rail station to serve as the San Francisco terminus for Caltrain and ultimately California High Speed Rail. While the idea for improving the Transbay Terminal had existed for a number of years, this potential for building transit capacity and new public space transformation was not envisioned in 1985 when the Downtown Plan was adopted. Realizing the Transit Center and other changes demand a new, fresh look at the land use, urban form, public space, and circulation policies and assumptions for the area. Moreover, while the Transit Center project is moving ahead, additional funding is still needed for the rail portion of the project.

Downtown San Francisco in the Context of Regional Growth

The future of the Transit Center District requires consideration of its place within the context of the larger city and the region as a whole. The growth and development patterns associated with the Transit District can advance larger regional sustainability goals.

One of the defining global issues of the 21st century is environmental sustainability. Patterns of human settlement, particularly land use and transportation, are a major component of sustainable development, as much as the ways we generate our energy, grow and consume our food, and produce and consume the products that fill our lives. The inefficient patterns of population growth spreading outward from urban centers in the past 60 years (i.e. “sprawl”) have produced immeasurable dilemmas for the Bay Area, the bioregion, the state, and beyond. As a result, the region is faced with diminishing recreational space, animal habitat, and farmland; increasing levels of congestion, air and water pollution; and increasing greenhouse gases, which lead to climate change effects, such as rising sea levels, erratic and disruptive weather patterns, and decreasing habitability of our local waters and lands for indigenous fish, land animals, and plants.

The Bay Area is now intensifying efforts to grapple with the question of sustainability, particularly steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without stifling growth. With the passage of AB 32 (which mandates statewide reductions in greenhouse gas emissions) and SB 375 (which requires regions to adopt growth management land use plans that result in reduced greenhouse gas emissions) in the California state legislature, and similar action on climate change likely at the federal level, there is increasing momentum to encourage transit-oriented development within every jurisdiction in the region and state.

Every urban center in the region is obligated to reassess its plans and potential changes within this context. Working with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) allocates targets for jobs and housing to every jurisdiction, based on regional growth projections for the next 25 years. In order to meet the targets of AB 32 and SB 375, ABAG has substantially increased growth allocations to all urban centers and transit-served locations in the region—particularly San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose. Downtown San Francisco has existing infrastructure in place that makes it a model of successful transit-oriented, low-impact growth. Adding development capacity to the downtown is a prudent step toward furthering the goal of reducing the State and region’s development footprint.

Many of these issues of controlled growth were understood in 1985, and reflected in the Downtown Plan. The core premise of the Downtown Plan was that a compact, walkable, and transit-oriented downtown is the key precondition for the successful and sustainable growth of the city and the region. The Transit Center District Plan furthers these principles and builds on them consistent with current conditions and context.

Land Use

The Land Use section outlines the evolving nature of land uses downtown and in the Transit Center District. It sets forth policies aimed at fulfilling a vision for the District as the city’s grand center, a symbol of the region’s vitality, with a dense mix of uses, public amenities, and a 24-hour character.

Introduction and Context

Since the adoption of the Downtown Plan in 1985, much of the area has been developed and multiple economic cycles have come and gone. Major growth has transformed portions of the downtown, particularly south of Market Street, expanding the downtown southward as directed by the Downtown Plan. In 1985, Mission Street was not regarded in any way as a prime downtown location; today, Mission Street is a premier address, an expansion of the city's Financial District. With new high-density downtown residential neighborhoods planned and starting to grow on the southern edge of the downtown, Mission Street and the Transbay Transit Center are fast becoming the geographic heart and center of the downtown, which now stretches from Rincon Hill and the Bay Bridge on the south to the Transamerica Pyramid on the north. The few remaining potential development sites in downtown are primarily near the Transbay Transit Center.

Downtown Growth in the Transit Center District

Maintaining a compact, walkable central business district, one that can be walked from end to end in about 20 minutes, is a core premise of the Downtown Plan. Compactness, particularly in relation to public transit, was recognized as one of the district’s chief assets. The Downtown Plan envisioned the area just south of Market Street around the Transbay Terminal not just as the primary growth area of the downtown, but as its hub.

A quarter of a century ago, during the preparation of the Downtown Plan, few downtown functions existed south of Market Street. The city was experiencing a major demand for office space and unless new policies were enacted, growth would continue to displace older important buildings in the business core north of Market. The Downtown Plan proposed and the City adopted new Planning Code provisions that landmarked dozens of important buildings and shifted office development to a special district with the city’s tallest height limits (at 550 feet) around the Transbay Terminal. Zoning was also structured to enable unused development rights from designated historic buildings throughout the downtown to be transferred to this district.

In recent years, development has occurred in the Transit Center District, and the goals and controls enacted in the Downtown Plan are being realized. The Transit Center District Plan is intended to build on the goals and principles of the Downtown Plan, and to continue to realize development potential and public investment in the Transit Center District.

Regional Environmental Sustainability and Downtown San Francisco

How people commute to work has dramatic implications for the region’s overall sustainability. More driving leads to more greenhouse gas emissions, lower air and water quality, more congestion on regional roads, and negative impacts on social equity and access to jobs (as jobs located away from public transportation are difficult to reach for lower income and transit-dependent people). Compared to other locations in the region, downtown San Francisco has far and away the highest share of workers commuting by means other than auto. Over 75 percent of all workers in the core part of the Financial District use transit to get to work, with only 17 percent driving or carpooling. Once a job is located outside of downtown, even within San Francisco, the percentage of transit users drops by half and the auto use rises equivalently. In downtown Oakland area, transit use is lower still. Outside of these major downtowns, the percentage of workers that do not drive to work is minuscule. Increasing the development capacity in the Transit Center District, as opposed to any other locality in the region (or city), will go further to support both local and regional goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reduce other environmental impacts without major additional regional transit investment beyond those already planned.

While concentrating both jobs and housing (and other uses) near major transit centers reduces auto travel, research has consistently shown a notably stronger correlation between auto travel and the proximity of jobs to transit than housing to transit. That is, workers, in determining whether to take transit or drive to work, are more sensitive to distance from major transit on the job end of the commute trip than on the home end. Research has also shown the threshold for job proximity to transit is not more than ½-mile from regional transit, whereas for housing it is one mile or more. This suggests that to maximize regional transit use and achieve the lowest overall auto travel, land immediately proximate to major regional transit (e.g. rail stations like BART or Caltrain) should be oriented more toward high-density jobs, with areas ringing these cores oriented more to high-density housing. Both areas should be mixed-use and pedestrian-oriented with a rich variety of supporting services (such as retail and community facilities), in order to create a vibrant and active district for residents, employees, and visitors. Most importantly, this research helps to confirm the land use mix envisioned in the Plan Area.

Objectives and Policies

The following objectives and policies are intended to achieve the vision set out for the Transit Center District as a high-density, vibrant employment center, with building heights, densities, FAR, and an engaging public realm appropriate to its place in the city.

OBJECTIVE 1.1

MAINTAIN DOWNTOWN SAN FRANCISCO AS THE REGION’S PREMIER LOCATION FOR TRANSIT-ORIENTED JOB GROWTH WITHIN THE BAY AREA.

OBJECTIVE 1.2

REINFORCE THE ROLE OF DOWNTOWN WITHIN THE CITY AS ITS MAJOR JOB CENTER BY PROTECTING AND ENHANCING THE CENTRAL DISTRICT’S REMAINING CAPACITY, PRINCIPALLY FOR EMPLOYMENT GROWTH.

OBJECTIVE 1.3

CONTINUE TO FOSTER A MIX OF LAND USES TO REINFORCE THE 24-HOUR CHARACTER OF THE AREA.

POLICY 1.1

Increase the overall capacity of the Transit Center District for additional growth.

For the core of the downtown business district where building heights are the tallest, overall development density is controlled primarily through FAR, and secondly through height and bulk limitations. For areas with the tallest height limits, the maximum physical envelope allowed or desired are often not attainable without acquiring and combining multiple contiguous parcels, which is often not possible or desirable. This condition leads to buildings that are not fully maximized in development intensity in the core area where it is most appropriate. There is currently a maximum cap of 18:1 FAR in the C-3-O and C-3-O (SD) districts. Rezoning the entire Plan area to C-3-O(SD) and eliminating the upper FAR limit will enable buildings to achieve the densities and heights envisioned in the Plan, with some reaching an FAR of over 30:1. As a result of lifting the FAR cap, controls for the physical envelope of the buildings will regulate the development density of the District. This step, however, will require even more thought on physical design quality and building envelope to ensure the maintenance of a livable and attractive downtown. New guidelines for design quality and building scale that build on existing controls and design guidelines are included in the Urban Form section of this Plan.

POLICY 1.2

Revise height and bulk limits in the Plan Area consistent with other Plan objectives and considerations.

While acknowledging the Plan’s premise that the overall development capacity of the District should be increased, height and bulk limits must be also shaped by considerations for urban form, key public views, street level livability, shadows on key public spaces, wind impacts, historic resources, and other factors. Height and bulk limits are discussed in more detail in the Urban Form section of the Plan.

POLICY 1.3

Encourage and permit non-residential uses on major opportunity sites.

In view of the limited number of sizable development sites in the District, which represent the bulk of the remaining office capacity in the downtown core, it is essential to allow major development sites to include a sizable commercial component.

Preserving office and job growth capacity is a major consideration, but so too is ensuring a mix of uses to help the area achieve a more 24-hour character. A mix of uses is generally desirable for very large projects. Additionally, the Plan recognizes that small lots are often not large enough to be developed with efficient office buildings, and some very large buildings contemplated in the Plan (i.e. taller than 600 feet) may be too large from a risk and market absorption standpoint to be devoted to a single use.

POLICY 1.4

Prevent long-term under-building in the area by requiring minimum building intensities for new development on major sites.

Major existing and planned investments in regional and local transit infrastructure and a limited capacity for added development make it unwise to permit new development to substantially under-build any of the few remaining major development sites in downtown. Moreover, under-building yields substantially lower revenues than necessary to help fund the Transit Center, affordable housing, streetscape improvements, and other area infrastructure.

POLICY 1.5

Consider the complexity and size of projects in establishing the duration for entitlements for large development projects.

Many development projects in the Plan Area are, by their very nature, large and complex. In the best of circumstances, it can take projects a year or two to finalize construction financing, complete the necessary drawings and documents, and complete final reviews with the necessary City agencies prior to actually commencing construction. Further, the fluctuations of local and wider economic conditions can slow down the completion of an approved project despite the best efforts of project sponsors to construct approved and desirable projects. Because of the size and complexity of many of the large projects in the Plan Area, these factors are magnified to necessitate longer lead times to reasonably realize these projects. Currently, planning entitlements are typically valid for three years (but some for as little as 18 months) prior to mandatory discretionary hearings to consider extensions. The City should evaluate all of the pertinent entitlement durations that may affect a project and consider adopting a uniform longer time-frame for entitlement validity, such as five years.

OBJECTIVE 1.4

ENSURE THE DISTRICT MAINTAINS AREAS THAT CONTAIN CONCENTRATIONS OF GROUND-LEVEL PUBLIC-SERVING RETAIL AND CONVENIENCE USES FOR WORKERS AND VISITORS.

OBJECTIVE 1.5

ACTIVATE ALLEYS AND MID-BLOCK PEDESTRIAN WALKWAYS WITH ACTIVE USES IN ADJACENT BUILDINGS TO MAKE THESE SPACES ATTRACTIVE AND ENJOYABLE.

POLICY 1.6

Designate certain select street frontages as active retail areas and limit non-retail commercial uses, such as office lobbies, real estate offices, brokerages, and medical offices, from dominating the street level spaces.

Establishing a vibrant public realm is a critical element of achieving the goals of the Transit District, such as supporting an active employment center, encouraging transit use, and creating a walkable and pedestrian-friendly street environment. While all streets and alleys should be pedestrian-oriented and feature active uses lining the ground floors, key streets and alleys to ensure active retail uses include 2nd Street, Natoma Street, and Ecker Street.

Urban Form

Urban form relates to the physical character of an area and the relationship of people and the landscape to the built environment. In the Transit Center District Plan Area, urban form is especially important as the intensity and height of buildings planned for the area greatly affects the character and quality of the city, and our experience of it at two levels: at both the cityscape level and at the ground level. Because of this, urban form within the Plan Area is considered at several scales, including building heights and their effect on the skyline and views, tower design, streetwall design, and the experience at the pedestrian level.

This section addresses the balance between maximizing development intensity in the Plan area to take advantage of proximity to good transit access and ensuring that the core objectives of urban form and livability are achieved— creating and maintaining a sense of place, protecting public views, and ensuring a pleasant and welcoming pedestrian environment.

The City adopted the Urban Design Element of the General Plan in 1972 and the Downtown Plan in 1985. These plans set out the policies that have achieved the characteristics of downtown San Francisco we enjoy today: a compact, human-scaled, walkable and dynamic urban center and a dramatic concentrated skyline set against the natural backdrop of the city’s hills. This section builds on the core principles of city form established in these two plans. It presents key objectives and policies for directing new development in a manner that enhances the overall cityscape and builds upon established and planned transit assets downtown.

Building Height and Skyline

San Francisco is renowned for its physical beauty and unique sense of place. These qualities are defined by buildings and streets laid upon hills and valleys, the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean, and signature landmarks poised at picturesque locations. This stunning assemblage—the rise and fall of hills, the backdrop of a downtown cityscape against the water and hills across the Bay, the iconic pairing of the Bay Bridge with the skyline—are enjoyed by residents and visitors viewing the city from its hills, streets, public spaces, and surrounding vantages. The city’s urban form at this scale is an essential characteristic of San Francisco’s identity. The city’s urban form:

-

Orients us and provides a sense of direction;

-

Imprints in our minds the physical relationship of one place to another, through features of topography, landscape, access, activity, and the built environment;

-

Distinguishes one area from another; and

-

Grounds us, providing reference points and reminding us of where we are.

When changes to the cityscape are considered, the goal is to build on and reinforce existing patterns and qualities of place that provide the city with its unique identity and character. The natural topography of the city is augmented by the man-made topography of its skyline, such as the concentrations of large buildings within downtown. Changes to the skyline, such as significant changes in allowable building heights, must be considered as if reshaping major elements of the city’s natural topography of hills and valleys, for this is the scale of change to the visual landscape that they represent. The undifferentiated spread of tall buildings without appropriate transitions, or without deference to the larger patterns, iconic and irreplaceable relationships, or to key views of defining elements of the area’s landscape, can diminish and obscure the city’s coherence and the collective connection of people to their surroundings.

The critical factors in the urban form at a larger scale are building height (and bulk) and the placement and orientation of tall buildings. While a building design may be gracious, well-articulated, and artistic in its own right, its placement, scale and orientation relative to the overall cityscape is equally, if not more, important. A building design and scale that may be appropriate in one specific location may not be appropriate if sited even one block away.

In addition to affecting the quality of place at the cityscape level, the size and placement of buildings significantly influence the quality of the city at the ground level. One specific effect of building height and location at ground level is sunlight access on streets and public spaces. San Franciscans have long expressed and continue to reinforce the importance of maintaining sunlight on streets and public spaces. As the Downtown Plan states, “As a forest becomes denser, it becomes more difficult to find a sunlit meadow. Similarly, in San Francisco's downtown, sunshine and wind protection, which are essential to the personal comfort of open space users, become of prime importance in the planning for downtown open space.” This is not to say that all potential shading of all public spaces should be avoided at all costs. What is of most concern is the shading of heavily-used open spaces during key usage times of the day and in key locations. Consistent with the procedures and standards adopted as part of the implementation of sunlight protection regulations, primarily Section 295 (“Prop K”) created by the voters, decision makers must weigh the Plan’s overarching public objectives against potential impacts. The urban form proposals of this Plan, particularly building height, are tailored where possible with an eye to this key ingredient of livability (i.e. without compromising the core Plan objectives for land use and the larger urban form).

The following objectives and policies address building height and skyline within the Plan area, with attention focused on creating a high quality urban form, at both the cityscape scale and on the ground.

OBJECTIVE 2.1

MAXIMIZE BUILDING ENVELOPE AND DENSITY IN THE PLAN AREA WITHIN THE BOUNDS OF URBAN FORM AND LIVABILITY OBJECTIVES OF THE SAN FRANCISCO GENERAL PLAN.

OBJECTIVE 2.2

CREATE AN ELEGANT DOWNTOWN SKYLINE, BUILDING ON EXISTING POLICY TO CRAFT A DISTINCT DOWNTOWN “HILL” FORM, WITH ITS APEX AT THE TRANSIT CENTER, AND TAPERING IN ALL DIRECTIONS.

OBJECTIVE 2.3

FORM THE DOWNTOWN SKYLINE TO EMPHASIZE THE TRANSIT CENTER AS THE CENTER OF DOWNTOWN, REINFORCING THE PRIMACY OF PUBLIC TRANSIT IN ORGANIZING THE CITY'S DEVELOPMENT PATTERN, AND RECOGNIZING THE LOCATION'S IMPORTANCE IN LOCAL AND REGIONAL ACCESSIBILITY, ACTIVITY, AND DENSITY.

OBJECTIVE 2.4

PROVIDE DISTINCT TRANSITIONS TO ADJACENT NEIGHBORHOODS AND TO TOPOGRAPHIC AND MAN-MADE FEATURES OF THE CITYSCAPE TO ENSURE THE SKYLINE ENHANCES, AND DOES NOT DETRACT FROM, IMPORTANT PUBLIC VIEWS THROUGHOUT THE CITY AND REGION.

OBJECTIVE 2.5

BALANCE CONSIDERATION OF SHADOW IMPACTS ON KEY PUBLIC OPEN SPACES WITH OTHER MAJOR GOALS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE PLAN, AND IF POSSIBLE, AVOID SHADING KEY PUBLIC SPACES DURING PRIME USAGE TIMES.

POLICY 2.1

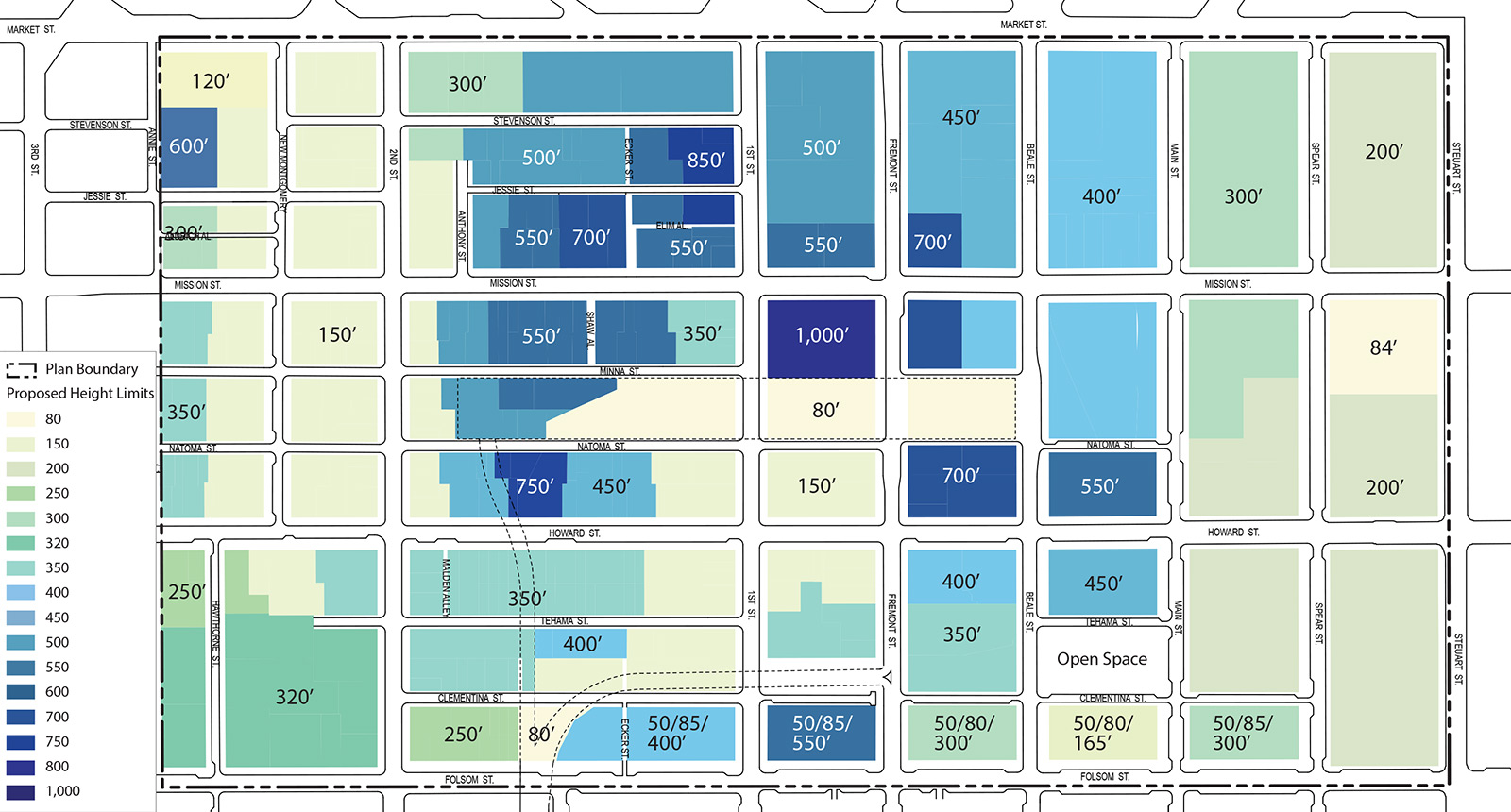

Establish the Transit Tower as the “crown” of the downtown core—its tallest and most prominent building—at an enclosed height of 1,000 feet.

As the geographic epicenter of downtown, as well as the front door of the Transbay Transit Center, the Transit Tower should be the tallest building on the city’s skyline. The Tower represents the City’s commitment to focusing growth around a sustainable transportation hub, as well as the apex of the downtown skyline. Additionally, the sheer prominence of this building will be a substantial benefit to the Transit Center itself, as 100 percent of the Transbay Terminal revenue from the sale or lease of the publicly-owned land for the Transit Tower development will be used for the funding of the Transit Center program. Based on visual simulations of urban form alternatives, a Transit Tower height of 1,000 to 1,200 feet (to the tip of the building’s tallest element) is appropriate and desirable.

The creation of a new crown to the skyline adjacent to the Transit Center is an important objective of the Plan. If the Transit Tower is built ultimately to a height of less than 900 feet or otherwise reasonably judged after a period of time unlikely to be built, the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors should consider rezoning one of the key sites near the corner of 1st and Mission Streets to a height of 1,000 feet.

FIGURE 2 - Proposed Height Limits

(Note: Height limits shown at 600 feet or taller are intended to indicate total building height as described further in Policy 2.7 and are not intended to allow for the ten percent tower height extensions allowed for the “S” bulk district. Height limits shown at lower than 600 feet are intended to remain in the “S” bulk district.)

POLICY 2.2

Create a light, transparent sculptural element to terminate the Transit Tower to enhance skyline expression without casting significant shadows. This vertical element may extend above the 1,000 foot height limit.

To ensure an elegant and unique sculptural termination to the top of the Transit Tower, an un-enclosed sculptural element that is consistent with the building's architecture and is set in a way that addresses shadow concerns is strongly encouraged.

POLICY 2.3

Create a balanced skyline by permitting a limited number of tall buildings to rise above the dense cluster that forms the downtown core, stepping down from the Transit Tower in significant height increments.

In order to create a skyline in all directions to enhance the downtown’s topographic “hill” form with graceful transitions in all directions, a small number of buildings should rise above a height of 600 feet—the downtown’s current maximum height limit—but at heights lower than the Transit Tower site. The number of these buildings greater than 600 feet in height should be limited and carefully sited to maintain sky visibility between them from key public vantage points and to prevent these buildings from visually merging into a single wide mass of great height.

One building of up to 850 feet in height is desirable between Market and Mission Streets, just west of First Street, sufficiently distanced from the Transit Tower, on the west side of First Street, north of Elim Alley. Should a building taller than 700 feet not be built in this zone within a sufficient amount of time, such as ten years, or otherwise reasonably judged unlikely to come to fruition, the City should consider reclassifying the 700-foot zone on the north side of Mission Street just west of Ecker Street to enable a building up to 850 feet to be constructed at that site.

Height transitions of at least 150 feet (e.g. 1000 to 850, 850 to 700, 700 to 550) are essential between major height tiers in order to create graceful and distinct transitions between buildings of such scale in this compact area. A more significant transition, however, is necessary in the southern portion of the District, where prevailing building heights in the districts immediately adjacent are lower. In this area, height limits should more quickly transition to 350 feet and lower.

POLICY 2.4

Transition heights downward from Mission Street to Folsom Street and maintain a lower “saddle” to clearly distinguish the downtown form from the Rincon Hill form and to maintain views between the city’s central hills and the Bay Bridge.

POLICY 2.5

Transition heights down to adjacent areas, with particularly attention on the transitions to the southwest and west in the lower scale South of Market areas and to the waterfront to the east.

The intent of the urban form changes introduced by the Rincon Hill Plan was to separate the Hill’s form from the downtown skyline. For all of the reasons discussed earlier in this section, maintaining a sense of place and orientation by distinguishing neighborhoods and districts on the skyline is important. The building heights of Rincon Hill and areas to the north were crafted to maintain a lower point, or “saddle” in the skyline between Howard Street and the north side of Folsom Street. This lower stretch on the skyline between the downtown core and Rincon Hill also provides important east-west views from the hills in the center of the city (e.g. Corona Heights, Twin Peaks, Upper Market) to the East Bay hills, the Bay Bridge, the Bay, and vice versa. This section of the skyline should achieve a height no taller than 400 feet. Equally important to stepping down buildings in the north-south direction, structures should also transition downward to adjacent lower scale neighborhoods and to the waterfront. Building heights should taper down to 250 feet and lower along the Second Street corridor to the southwest.

POLICY 2.6

Ensure a minimum height requirement for the Transit Tower site, as well as other adjacent sites zoned for a height limit of 750 feet or greater.

The ultimate height of the occupied portion of the building proposed for the Transit Tower (and other buildings) will be affected largely by the market. To achieve the urban form goals of the Plan, it is critical that this building be the crown of the skyline. If, for whatever reason, the Transit Tower is proposed for an occupied height lower than the maximum height allowed, the building should include an architectural feature that extends the effective height of the building in some form to a height of at least 950 feet.

POLICY 2.7

Establish controls for building elements extending above maximum height limits to incorporate design considerations and reduce shadow impacts.

The typical height limit rules that apply to buildings in the C-3 and in the S bulk districts which allow tower extensions and that govern architectural elements at the tops of buildings should not apply to buildings taller than 650 feet or where height limits are greater than 550 feet. Instead, specific rules should be crafted to apply to such tall buildings to reflect their central and iconic positions on the skyline in order to enhance their appearance while minimizing potential visual and shadow impacts.

Building Design: Tower Zone

The Transit Center District will be home to several of the tallest buildings in San Francisco. Because these buildings affect the street environment, access to sun and sky, and the skyline, the massing and design of towers is critical to achieving the overall urban form goals for the Plan area. With this in mind, the following objectives and policies address the massing and scale of tall buildings within the District.

OBJECTIVE 2.6

PROVIDE FLEXIBILITY AND SUFFICIENT ALLOWANCE FOR THE STRUCTURAL CORE OF TALL BUILDINGS (TALLER THAN 600 FEET), WHILE ENSURING THAT THE BUILDINGS MAINTAIN ELEGANT AND SLENDER PROPORTIONS AND PROFILE.

OBJECTIVE 2.7

ENSURE ARTICULATION AND REDUCTION TO THE MASS OF THE UPPER PORTIONS AND TOPS OF TOWERS IN ORDER TO CREATE VISUAL INTEREST IN THE SKYLINE AND HELP MAINTAIN VIEWS.

OBJECTIVE 2.8

MAINTAIN SEPARATION BETWEEN TALL BUILDINGS TO PERMIT AIR AND LIGHT TO REACH THE STREET, AS WELL AS TO HELP REDUCE ‘URBAN CANYON’ EFFECTS.

Do not limit the floorplate or dimensions of the lower tower for buildings taller than 550 feet.

POLICY 2.9

Require a minimum 25 percent reduction in the average floorplate and average diagonal dimension for the upper tower as related to the lower tower.

For the purposes of this Plan, towers are divided vertically into two main components: the Lower Tower (generally defined as the lower 2/3 of the tower) and Upper Tower (the upper 1/3 of the tower). For buildings taller than 650 feet, there should be no bulk controls for the Lower Tower. However, adherence to tower separation rules is critical and exceptions to them must be limited. To reduce bulk at the highest levels, a 25 percent floorplate reduction and 13 percent average diagonal reduction is required for the Upper Tower portion of tall buildings.

POLICY 2.10

Maintain current tower separation rules for buildings up to 550 feet in height, extend these requirements for buildings taller than 550 feet, and define limited exceptions to these requirements to account for unique circumstances, including adjacency to the Transit Center and to historic structures.

Building Design: Streetwall and Pedestrian Zone

The character of a district is largely defined by the scale of the roadway, sidewalks, and adjoining building frontages. Collectively, these shape the pedestrian experience by creating a sense of enclosure, often called an "urban room." The Transit District will contain many of the city's tallest buildings and buildout of the District will entail replacement of many smaller buildings that now provide a humane scale. Without moderation and articulation of the lower portions of tall buildings, the result could lack pedestrian references that create a comfortable experience at the ground level. Therefore, it is particularly critical that buildings be designed in a thoughtful manner, taking into consideration the street scale and pedestrian interest in the massing of tall buildings, not simply be designed as architectural gestures of the skyline. In addition, the ground floors must foster a lively and attractive pedestrian experience. In guiding building design in the Plan Area, the following policies address two main building zones:

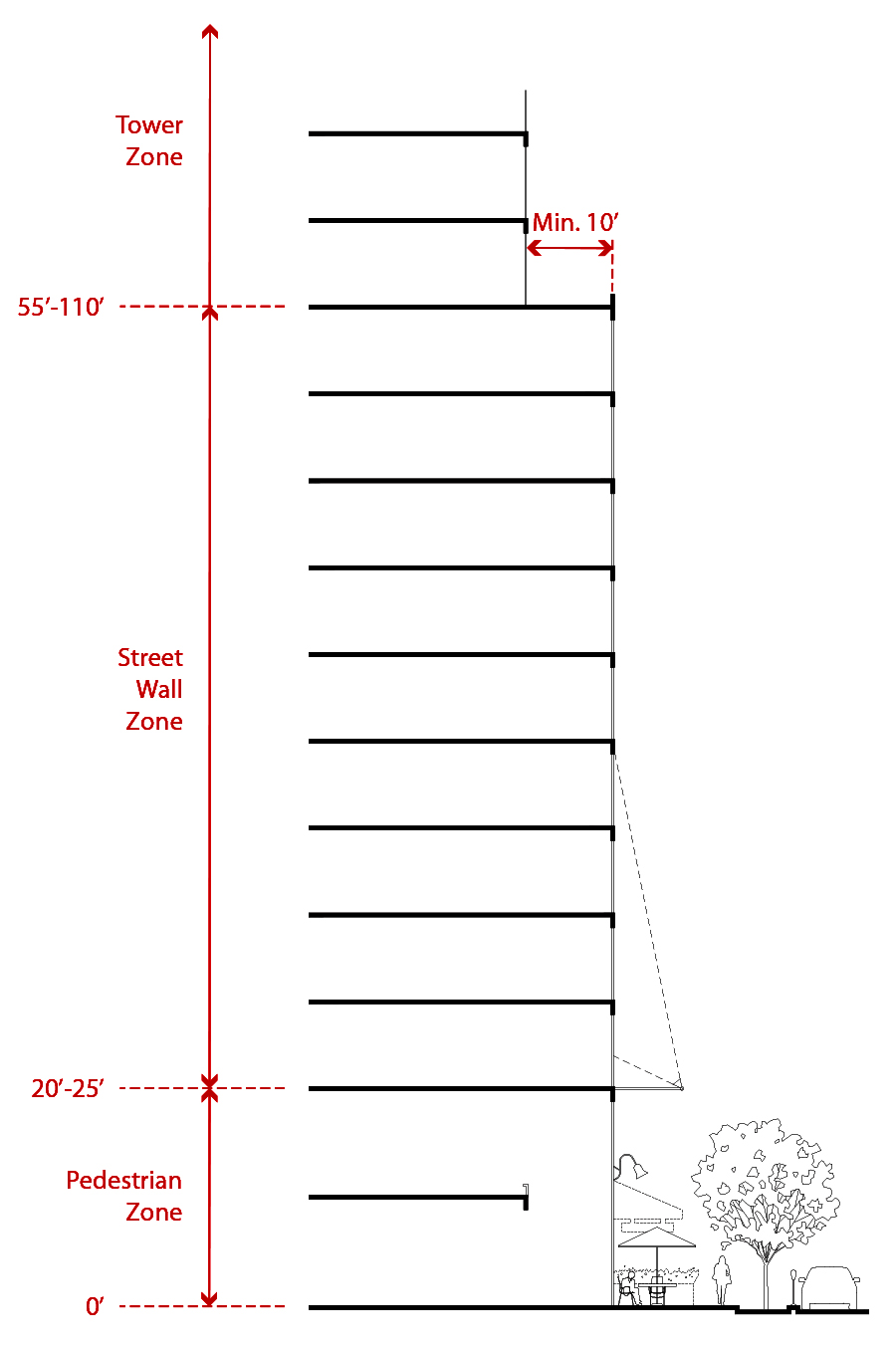

Streetwall Zone. The height of the streetwall, generally its relation to the street width, is a defining characteristic of a neighborhood’s scale. Within the Transit Center District, the streetwall is defined as that part of the building above the pedestrian zone and extending to a height of 55 to 110 feet (depending on the context).

Pedestrian Zone. Pedestrians are most aware of the first two to three stories at the ground, or what is within their immediate view. These policies focus on the character of the street and how buildings meet the ground. The pedestrian zone is defined as the first 20–25 feet of a building.

Streetwall Zone

OBJECTIVE 2.9

PROVIDE BUILDING ARTICULATION ABOVE A BUILDING BASE TO MAINTAIN OR CREATE A DISTINCTIVE STREETWALL COMPATIBLE WITH THE STREET’S WIDTH AND CHARACTER.

OBJECTIVE 2.7

MAINTAIN APPROPRIATE CHARACTER-DEFINING BUILDING SCALE IN THE HISTORIC DISTRICT.

POLICY 2.11

Ensure that buildings taller than 150 feet in height establish a distinct base element to define the street realm at a comfortable height of not more than 1.25 times the width of the street.

Buildings with sheer facades rising up straight from the ground without a horizontal break at the streetwall height create a vertiginous and inhuman scale, particularly when grouped without intervening lower scale buildings. Unlike the Financial District area north of Market Street where numerous historic buildings of moderate scale remain interspersed between taller buildings, the core parts of the Transit Center District (such as along Mission Street) where likely development sites exist have only a few significant older buildings of modest scale (i.e. 50 to 100 feet in height). The Downtown Plan contains a policy to require a horizontal element (e.g. a belt course) on the façade in a manner that suggests a human-scaled building base, but this architectural feature alone is insufficient. Towers that incorporate upper story setbacks to define a distinctive base element or that distinctly taper away from the streetwall above the base height help to create a comfortable pedestrian environment, one that is more scaled to the human perspective at the street level. For the Transit Center District, a streetwall height of 55 to 110 feet defines a comfortable “urban room,” based on a prevailing street width of 82.5 feet. Where project sites are large enough to incorporate multiple buildings along the street face, including both tall towers and lower scale buildings of 150 feet in height or less, the towers themselves may not necessarily need to feature setbacks. However, where projects consist of a single tall building at the street face, even if accompanied by an adjacent open plaza, such towers should meet the articulation requirements described above. At least 60 percent of the building frontages on each block face should feature a distinct base that contributes to creating the urban room.

FIGURE 3 - Streetwall and Pedestrian Zone

POLICY 2.12

Where construction of the downtown rail extension must unavoidably demolish buildings, reduce impacts on the District’s character by facilitating appropriate re-use of these parcels.

The underground downtown rail extension is planned under Second Street curving eastward into the basement of the Transit Center. While the Second Street construction can be executed within the right-of-way, the necessary curvature alignment and widening of the tracks into the Transit Center necessitate the full or partial acquisition of several private parcels at both the northeast and southeast corners of Second and Howard streets, including the demolition of several buildings. It is important to ensure a positive re-use of these sites so that the district is not left with awkward or minimally-usable parcels. Because of the unique situations caused by the train’s alignment affecting both sides of Howard Street, the Plan proposes the following distinct responses:

Northeast Corner: The extent of the below-grade alignment and complexity of the track and station infrastructure challenges the feasibility of significant development at this corner. As a result, the best possible use of these parcels is the creation of a new public open space that facilitates pedestrian flow to the Transit Center and provides both a needed additional ground level open space and an opportunity for a major public vertical access to the rooftop Transit Center park. The design of the plaza should also incorporate architectural elements at the street edge that connect the plaza to the fabric of the historic district. The Public Realm section provides more detail on this concept.

Southeast Corner: The eastern edge of the underground track alignment slices diagonally across the three parcels north of Tehama Street and west of Malden Alley, with little possibility of constructing a building with foundations or columns immediately above the tracks. The remaining developable portion of the parcels east of the tracks totals approximately 9,000 square feet, though in a somewhat awkward wedge configuration. Given the potential for a plaza at the more appropriate northeast corner of this intersection adjacent to the Transit Center, a new building should be encouraged on this site to maintain the physical continuity of the historic district along Second and Howard streets. Though it may not possible to construct building foundations above the rail tunnel on this site, a new building here should strive to create a prominent corner presence at Second and Howard.

To make a new building more feasible given the shape and size of the site that remains after the Downtown Rail Extension right-of-way needs are met, the City should consider vacating Malden alley in order to permit a merger with the affected properties along Second Street. The General Plan includes policies (Urban Design Element Policies 2.8–2.10) discouraging the vacation of public-rights-of-way except under unique and extraordinary circumstances in which the demonstrable public benefit of a proposed project requiring the vacation substantially outweighs the loss in public value (both current and potential) of maintaining the right-of-way in public ownership. In this unique circumstance, vacating Malden could aid in the positive transition of this block in light of the rail alignment. Consequently, at an appropriate point following completion of arrangements with the TJPA to secure the necessary property for the rail alignment and submittal of a building proposal, vacation of Malden should be considered consistent with the General Plan vacation policies along with demolition of the subject buildings along Second Street. If the extent of the rail alignment necessitates taking more of the parcels along 2nd Street than is currently planned, a major development would be unlikely on these sites and the rationale for vacating Malden Alley may not be justifiable.

OBJECTIVE 2.11

PURSUE BUILDING SETBACKS TO AUGMENT A SIDEWALK WIDENING PROGRAM ON STREET FRONTAGES WHERE SIGNIFICANT CONTIGUOUS STRETCHES OF PARCELS ARE LIKELY TO BE REDEVELOPED.

In some areas within the Transit Center District, the program for widening sidewalks can be augmented by requiring building setbacks. Such treatment, however, is only appropriate where there are contiguous stretches of anticipated new development, such as those listed and in those situations where the result would not create a “sawtooth” pattern of building frontages at the sidewalk. When utilized, building setbacks must be designed as a seamless extension of the sidewalk.

POLICY 2.13

As appropriate on a case-by-case basis, require new buildings located at major street corners (outside of the Conservation District) in the Plan Area to modestly chamfer the corner of the building at the ground level (if the building is otherwise built out to the property line) in order to provide additional pedestrian space at busy corners.

POLICY 2.14

Require building setbacks for new buildings to expand the roadway where necessary to accommodate needed transit, bicycle and pedestrian facilities.

A minimum setback of at least 12.5 feet should be required on the following frontage:

- South side of Mission Street between First and Fremont streets (Transit Tower).

This is necessary to accommodate new roadway configuration for Mission Street on this block that includes a transit boarding island while still maintaining the necessary sidewalk width (e.g. 20’) in front of the tallest building in the City and the busy Transit Center hub.

Consider requiring a building setback of up to ten feet on the following frontages if development proceeds such that a desirable pattern of buildings would result:

- North side of Mission Street between First and Second streets

- North side of Howard Street between First and Second streets

- West side of First Street between Market and Mission streets

Pedestrian Zone

Buildings in the Transit Center District should be designed at where they meet the ground, in such a way that reinforces the human scale. Ground floor uses and building features such as entries, building materials, canopies and awnings, display windows, and lighting, all contribute to conditions ideal for attracting pedestrian activity. To that end, the following policies apply to the pedestrian zone of all buildings within the District.

OBJECTIVE 2.12

ENSURE THAT DEVELOPMENT IS PEDESTRIAN-ORIENTED, FOSTERING A VITAL AND ACTIVE STREET LIFE.

OBJECTIVE 2.13

ENACT URBAN DESIGN CONTROLS TO ENSURE THAT THE GROUND-LEVEL INTERFACE OF BUILDINGS IS ACTIVE AND ENGAGING FOR PEDESTRIANS, IN ADDITION TO PROVIDING ADEQUATE SUPPORTING RETAIL AND PUBLIC SERVICES FOR THE DISTRICT.

OBJECTIVE 2.14

ENCOURAGE TALL AND SPACIOUS GROUND FLOOR SPACES.

OBJECTIVE 2.15

ENCOURAGE ARTICULATION OF THE BUILDING FAÇADE TO HELP DEFINE THE PEDESTRIAN REALM.

OBJECTIVE 2.16

MINIMIZE AND PROHIBIT BLANK WALLS AND ACCESS TO OFF-STREET PARKING AND LOADING AT THE GROUND FLOOR ON PRIMARY STREETS TO HELP PRESERVE A SAFE AND ACTIVE PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT.

POLICY 2.15

Establish a pedestrian zone below a building height of 20 to 25 feet through the use of façade treatments, such as building projections, changes in materials, setbacks, or other such architectural articulation.

Combined with upper level setbacks to define the streetwall, emphasizing the ground floor of a building can help create a more interesting and comfortable streetscape and pedestrian environment.

POLICY 2.16

Require major entrances, corners of buildings, and street corners to be clearly articulated within the building’s streetwall.

POLICY 2.17

Allow overhead horizontal projections of a decorative character to be deeper than one foot at all levels of a building on major streets.

POLICY 2.18

Limit the street frontage of lobbies and require the remaining frontage to be occupied with public-oriented uses, including commercial uses and public open space.

Expansive lobby frontages do not activate the street or contribute to an engaging pedestrian experience and can negatively dampen and discourage the life and character of the district. Frontages where lobbies are minimized in width (but prominent) at the street face can be lined with active spaces, such as commercial uses and public space, creating an engaging pedestrian experience. Lobbies should be limited to 40 feet in width or 25 percent of the street frontage of the building, whichever is larger.

POLICY 2.19

Discourage the use of arcades along street frontages, particularly in lieu of setting buildings back.

Arcades are generally not an appropriate design solution within the Transit Center District, as they can deaden the sidewalk environment by separating a building’s ground floor from the street by a wall of columns. Additionally, as development sites are generally not contiguous along an entire block and are interspersed with existing buildings, arcades remain as truncated non-continuous paths of travel and so are generally avoided by pedestrians whose destinations are other than the immediate building. In addition, San Francisco’s cool, temperate climate often results in empty, little-used arcades in Downtown which, because they are carved out of the building face at the ground level, do not receive direct sunlight. In climates that are warmer or wetter than San Francisco’s, arcades can be a more practical and valuable addition to the urban environment.

POLICY 2.20

Require transparency of ground-level facades (containing non-residential uses) that face public spaces.

Opaque window treatments and the placement of mechanical building features (even if camouflaged) on the façade within the pedestrian zone effectively act as blank walls that have a deadening presence along the street. By encouraging maximum ground floor transparency, this policy aims to increase the liveliness of the pedestrian realm.

POLICY 2.21

Limit the width of the individual commercial frontages on 2nd Street to maintain a dense diversity of active uses.

Second Street is the retail center of the District, characterized by many small shops and services lining the sidewalks. This pattern enables people to find a wide variety of stores and services meeting their needs and to stroll along the sidewalks browsing for restaurants and services that fit their needs. This diversity of small uses ensures a lively and vibrant district. It is important to ensure the continuance of this pattern. Ground floor spaces must be articulated into storefronts with multiple entryways. Larger floor plate uses should be wrapped by other commercial spaces such that no more than 75 linear feet of one street frontage is occupied by a single commercial space. All façades should have multiple entrances and be highly transparent.

POLICY 2.22

Prohibit access to off-street parking and loading on key street frontages. Whenever possible, all loading areas should be accessed from alleys.

Maintaining the continuity of the pedestrian environment is paramount in this busy district, as is ensuring efficient movement of transit. In order to promote active street frontages and prevent vehicular conflict with sidewalk activity and transit movement, access to off-street parking and loading should be prohibited or restricted on key streets. Please see Policy 3.9 in the Public Realm section for more detail.

Building Design: Materials

The smart use of building materials can contribute greatly to the livability and sustainability of a place. The Downtown Plan addresses this notion by stressing the importance of using consistent building materials to create a visually interesting and harmonious building pattern. This Plan builds on this by encouraging the treatment of wall surfaces, such as with plants and light coloring, to further the District’s urban design and sustainability goals.

OBJECTIVE 2.17

PROMOTE A HIGH LEVEL OF QUALITY OF DESIGN AND EXECUTION, AND ENHANCE THE DESIGN AND MATERIAL QUALITY OF THE NEIGHBORING ARCHITECTURE.

POLICY 2.23

Assure that new buildings contribute to the visual unity of the city.

For the most part, buildings in San Francisco are light in tone and harmonize to form an elegant and unified cityscape. The overall effect, particularly under certain light conditions, is that of a white city laid over the hills, contrasted against the darker colors of the Bay and the vegetated open spaces and hilltops.

POLICY 2.24

Maximize daylight on streets and open spaces and reduce heat-island effect, by using materials with high light reflectance, without producing glare.

POLICY 2.25

Encourage the use of green, or “living,” walls as part of a building design in order to reduce solar heat gain as well as to add interest and lushness to the pedestrian realm.

Public Realm

The public realm is the shared space of a city—its streets, alleys, sidewalks, parks, and plazas. It is through these spaces that we experience a city, whether it is walking to work, shopping, or having lunch in a sunny plaza. A high quality public realm is fundamental in our perception of what makes a place special. Sufficient sidewalk widths and open spaces, along with streetscape elements, such as lighting, street furniture, and plantings, all play a big role in the character, comfort, and identity of place.

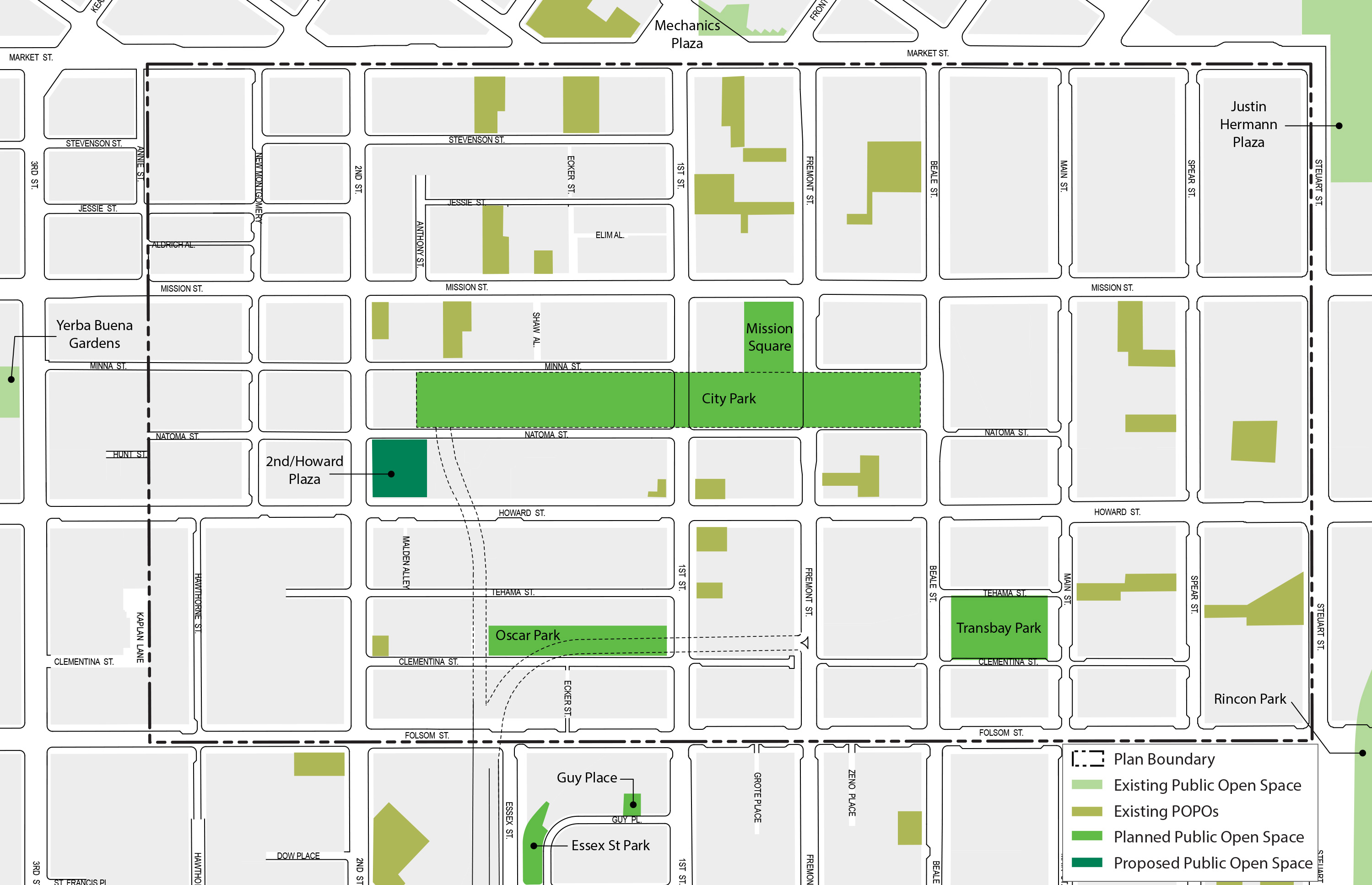

San Francisco’s Transit Center District is poised to become the heart of the new downtown, and with that comes the responsibility of creating an inviting, lively public realm that not only accommodates more people, but also creates a wonderful place, one that showcases the importance of this part of the city. To reach this goal, the Plan Area, which today is rather bleak and dominated by heavy traffic, will need to be significantly transformed. Most of the streets are designed for cars traveling to and from the Bay Bridge and regional highways, and as a result, the street environment is unattractive, with long blocks, few pedestrian amenities, and poor sidewalk conditions. In addition, open space in the area is comprised of small, dispersed, privately-managed spaces on individual sites. While there are a handful of major parks nearby, such as Yerba Buena Gardens and Rincon Park, the Plan area itself lacks any significant public open space.

Within the next 10 to 20 years, the Transit Center District will see exponential increases in pedestrian volumes, making it one of the busiest areas, if not the busiest, in downtown. Two separate factors will substantially contribute to the increased pedestrian volume—land use intensification and the Transbay Transit Center itself. Adding nine million square feet of building space to these concentrated blocks will result in a density greater than that of the Financial District to the north. Furthermore, the Transit Center will attract great volumes of train and bus users throughout the day, particularly during peak hours. The downtown extension of Caltrain and the future California High Speed Rail, each running multiple trains per hour in the peak, and with capacities approaching or exceeding 1,000 passengers per train, will add thousands of people to sidewalks, corners, and crosswalks, in a downtown neighborhood already experiencing new development and growth.

To fulfill the vision of an unsurpassed pedestrian-friendly place that supports the circulation and social needs of the District, the Plan proposes substantial changes in the design and allocation of the limited right-of-way space. These necessary changes include widening sidewalks (which can largely be achieved only by shifting allocation of roadway space from autos), adding mid-block crossings at key locations, and enhancing alleys as pedestrian spaces.

Augmenting the system of public ways, well-designed parks and plazas of sufficient size and distribution are essential to the function and livability of the downtown. These spaces provide room for socializing, eating lunch, taking quiet breaks from one’s day, providing facilities for recreational and cultural diversion, supporting the needs of local residents, and performing ecological functions. Above all, such spaces encourage locals and visitors alike to spend time downtown, activating the area throughout the day and year. As population and densities within the District increase, open space becomes an essential neighborhood amenity and a counterbalance in the built environment. The proposed 5.4-acre rooftop Transit Center Park will be a crucial component in meeting downtown’s open space needs. Additional open space amenities will be needed to augment this space and weave it into the neighborhood. To begin addressing this, the Plan proposes a new public plaza on the northeast corner of Howard and Second Streets. Besides providing additional street-level public space, the plaza will act as an important visual and physical connector to the Transit Center and the Transit Center Park.

Pedestrian Environment and Circulation

Aside from outlining a public realm and circulation system to support the Plan’s proposed intensified land use program, another key objective is to create a public realm that complements the major regional transportation infrastructure and service changes coming to the area. The District’s centerpiece, the Transit Center, will be a symbol of a new neighborhood that prioritizes transit and pedestrians. Along with an increase in development, this world-class multi-modal station will generate an unprecedented amount of pedestrian activity in the Plan Area.

To create a public realm worthy of a great city, as well as accommodate the increased number of pedestrians and transit users, the balance of space must shift more toward people on the street. To do this, the Plan envisions widened sidewalks with significant amenities and enhanced landscaping, and an overall cohesive streetscape design for the District. Unavoidably, this step involves certain tradeoffs between pedestrian improvements and space for automobiles. Wider sidewalk widths can feasibly be provided only through expanding the sidewalk into the roadway, removing on-street parking or traffic lanes, and to a lesser extent by narrowing traffic lanes. Giving priority to pedestrians and the Transit Center District’s place in the city means difficult choices in view of space limitations in the rights-of-way. The only other alternative is to require setbacks for all new buildings; however, such a policy would result in an entirely uneven and inconsistent sidewalk space since the relatively few likely building sites are dispersed and many buildings will remain in place. As a result, requiring building setbacks in this context is not a viable strategy for creating the consistent sidewalk widths and streetscape infrastructure envisioned as necessary for the District.

OBJECTIVE 3.1

MAKE WALKING A SAFE, PLEASANT, AND CONVENIENT MEANS OF MOVING ABOUT THROUGHOUT THE DISTRICT.

OBJECTIVE 3.2

CREATE A HIGH-QUALITY PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT IN THE DISTRICT CONSISTENT WITH THE VISION FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF A WORLD-CLASS CITY.

OBJECTIVE 3.3

GRACIOUSLY ACCOMMODATE INCREASES IN PEDESTRIAN VOLUMES IN THE DISTRICT.

OBJECTIVE 3.4

EMPHASIZE THE IMPORTANCE OF STREETS AND SIDEWALKS AS THE LARGEST COMPONENT OF PUBLIC OPEN SPACE IN THE TRANSIT CENTER DISTRICT.

POLICY 3.1

Create and implement a district streetscape plan to ensure consistent corridor-length streetscape treatments.

POLICY 3.2

Widen sidewalks to improve the pedestrian environment by providing space for necessary infrastructure, amenities and streetscape improvements.

A consistent program of landscaping is essential in creating a well-appointed downtown area. The streets in the District, particularly key streets such as Mission Street, are generally barren of necessary streetscape infrastructure, including trees, landscaping, benches, pedestrian lighting, bicycle racks, waste receptacles, news racks, kiosks, vendors, and other elements. Additionally, transit shelters and stops create serious pinch points that congest sidewalks. A consistent curb zone of at least six feet in addition to space allocated for circulation is necessary on all streets to accommodate these elements. Additional space is also necessary for improved curbside transit stops that meet minimum contemporary standards for passenger amenity but do not impinge on sidewalk circulation (as current bus shelters do). In addition to enhancing the quality of life for pedestrians, workers, residents, and visitors, green infrastructure creates necessary ecological features aimed at issues of stormwater flow and retention, air quality, urban heat islands, habitat, and other aspects.

POLICY 3.3

Facilitate pedestrian circulation by providing sidewalk widths that meet the needs of projected pedestrian volumes and provide a comfortable and safe walking environment.

Without substantial sidewalk widening throughout the district, pedestrian conditions would further degrade and result in uncomfortable or even unsafe conditions, particularly at street corners. Sidewalk and corner crowding can cause uncomfortable or unpleasant walking conditions: an inability to walk at a preferable speed to fit one’s needs (either leisurely or hurriedly), to walk abreast with companions, to stop and chat or look in shop windows, to avoid physical contact with other people, or to pass others. Added sidewalk widths throughout the District will accommodate anticipated pedestrian traffic, allow for a coordinated program of streetscape amenities and improvements, as well as provide areas for sidewalk cafes and retail displays. The minimum width necessary throughout the district to accommodate pedestrian circulation is 15 feet, exclusive of space for sidewalk amenities and infrastructure (e.g. transit shelters, trees, landscaping, benches, kiosks).

As described in preceding policies, sidewalks in the district need to be wide enough to allow for comfortable circulation and for streetscape infrastructure. The typical sidewalk in the district therefore should be at least 21 feet in width.

POLICY 3.4

Amend the Downtown Streetscape Plan to reflect sidewalk width and streetscape changes proposed in the Transit Center District Plan.

POLICY 3.5

Continue the Living Streets treatment to create linear plazas along Beale, Main, and Spear streets.

The “Living Streets” concept established in the Rincon Hill Plan and Transbay Redevelopment Plan should be extended into and through the Transit Center District area as originally envisioned in those plans. The design strategy of Living Streets reduces the number of traffic lanes, generally to two travel lanes plus parking, in order to significantly widen the pedestrian space on one side of the street (to approximately 30 feet in width), effectively creating a linear open space with significant amenities. As part of the Transit Center District Plan, this streetscape treatment on Beale, Main, and Spear Streets is extended north of Folsom to Market Street, creating significant green linkages from Market Street south past the Transbay Park in Zone 1 and through the new residential neighborhoods.

As the neighborhood character changes from Bryant Street to Market Streets, however, so shall the character of the Living Streets. South of Howard, pocket parks, seating areas, and community gardens in the linear open space complement adjacent residential uses. From Howard to Market Streets, the design emphasis of Beale, Main, and Spear Streets will focus more on hardscape elements and active uses (e.g. kiosks, bicycle sharing pods, café seating). By creating a linear open space stretching from Bryant Street to Market Street, the Living Streets weave two neighborhoods together, while creating an open space amenity in a very dense part of the city.

POLICY 3.6

Create additional pedestrian capacity and shorten pedestrian crossing distances by narrowing roadways and creating corner curb bulbouts.

Curb-to-curb distances on streets within the Transit Center District average between 50 and 60 feet, with multiple traffic lanes. For pedestrians, these wide streets can be unpleasant and potentially unsafe to cross. Widening sidewalks and removing travel or parking lanes on most of the District’s streets would significantly shorten the distance pedestrians must cross. Where on-street parking would remain, the curb at intersections can be extended to further reduce crossing distances while providing more pedestrian queuing capacity and reducing vehicle turning speeds. On streets where sidewalks cannot be widened sufficiently, corner bulbouts can provide critical expansion of queuing capacity for pedestrians, as corners are the most congested and impacted pedestrian locations. Where there is on-street parking, corner sidewalk extensions also make pedestrians more visible to drivers. The design of bulb-outs must be consistent with the adopted standards in the Better Streets Plan.

POLICY 3.7

Enhance pedestrian crossings with special treatments (e.g. paving, lighting, raised crossings) to enhance pedestrian safety and comfort, especially where bulb-outs cannot be installed.

In certain cases, specific bus movements make the installation of bulb-outs infeasible. In other cases, such as portions of First, Beale, and Main streets, on-street parking is subject to peak-hour parking restrictions in order to provide additional auto travel capacity. In these instances, special attention should be paid to the design of crosswalks to enhance their visibility and safety. Design strategies could include special paving treatments, highly visible crossing markings, flashing light fixtures, or illuminated signs.

Particularly at the ends of alleys where they meet major streets, raised crosswalks at sidewalk level should be created across the mouth of the alley. These features would emphasize to drivers that they are entering a special, slower zone in the alley and also heighten driver awareness of pedestrians at major streets as vehicles leave the alley.

POLICY 3.8

Develop “quality of place” and “quality of service” indicators and benchmarks for the pedestrian realm in the district, and measure progress in achieving benchmarks on a regular basis.

Similar to the current practice of measuring the function of right-of-ways for vehicles, steps should be taken to measure the quality of streets as both walking corridors and social spaces for people. For pedestrians, a legitimate indicator system would go beyond the suitability of sidewalks, comfort, and safety to empirically measure the amount and quality of human and social life on the street. The only measurement currently used for pedestrians is a version of “Pedestrian Level of Service” that assesses crowding conditions. Yet it is only one measure of pedestrian quality. Factors that should be considered in assessing the quality of the public realm include characteristics of adjacent motor vehicle traffic, aesthetic quality of the environment, amount and prevalence of pedestrian amenities, continuity of active uses in adjacent buildings, distance between link choices, and a thorough accounting for the differing types of activities that people engage in (or don’t engage in) on the street, such as chatting, sitting, window-shopping, reading, eating, and so forth. These measurements allow planners to identify problems, establish performance indicators, and highlight deficiencies, improvements, and results. The City needs to periodically monitor, qualitatively and quantitatively, the pedestrian environment to ensure that the policies and goals of the Plan are met.

OBJECTIVE 3.5

RESTRICT CURB CUTS ON KEY STREETS TO INCREASE PEDESTRIAN COMFORT AND SAFETY, TO PROVIDE A CONTINUOUS BUILDING EDGE OF GROUND FLOOR USES, TO PROVIDE A CONTINUOUS SIDEWALK FOR STREETSCAPE IMPROVEMENTS AND AMENITIES, AND TO ELIMINATE CONFLICTS WITH TRANSIT.

Multiple curb cuts along a street can have several negative effects on the pedestrian experience. Not only do they create inactive sidewalks, they become a significant hazard for pedestrians, who must maneuver around cross traffic. Curb cuts, moreover, remove valuable right-of-way space for trees, bicycle parking, and other pedestrian amenities. By limiting curb cuts on key streets, the Plan creates a safer and more attractive pedestrian environment for downtown users.

POLICY 3.9

Designate Plan Area streets where no curb cuts are allowed or are discouraged. Where curb cuts are necessary, they should be limited in number and designed to avoid maneuvering on sidewalks or in street traffic. When crossing sidewalks, driveways should be only as wide as necessary to accomplish this function.

No curb cuts to access off-street parking and loading should be allowed on key streets designated as priority thoroughfares for pedestrians, transit and continuous ground-floor retail. These include Second and Mission streets, the main north-south and east-west connectors in the District, respectively. The Plan extends the Transbay Redevelopment Plan’s and Rincon Hill’s curb cut restrictions on Folsom from Essex to Second Street, further strengthening its key function as a neighborhood retail and pedestrian spine. New curb cuts should also restricted on several alleys—Ecker, Shaw, and Natoma—that currently function or are envisioned as active pedestrian passageways. While not prohibited, new curb cuts should be strongly discouraged on First and Fremont Streets, especially on blocks that have alley access, and should require discretionary approval (e.g. Conditional Use) in all instances.

OBJECTIVE 3.6

ENHANCE THE PEDESTRIAN NETWORK WITH NEW LINKAGES TO PROVIDE DIRECT AND VARIED PATHWAYS, TO SHORTEN WALKING DISTANCES, AND TO RELIEVE CONGESTION AT MAJOR STREET CORNERS.

OBJECTIVE 3.7

ENCOURAGE PEDESTRIANS ARRIVING AT OR LEAVING THE TRANSIT CENTER TO USE ALL ENTRANCES ALONG THE FULL LENGTH OF THE TRANSIT CENTER BY MAXIMIZING ACCESS VIA MID-BLOCK PASSAGEWAYS AND CROSSWALKS.

OBJECTIVE 3.8

ENSURE THAT NEW DEVELOPMENT ENHANCES THE PEDESTRIAN NETWORK AND REDUCES THE SCALE OF LONG BLOCKS BY MAINTAINING AND IMPROVING PUBLIC ACCESS ALONG EXISTING ALLEYS AND CREATING NEW THROUGH-BLOCK PEDESTRIAN CONNECTIONS WHERE NONE EXIST.

OBJECTIVE 3.9

ENSURE THAT MID-BLOCK CROSSWALKS AND THROUGH-BLOCK PASSAGEWAYS ARE CONVENIENT, SAFE, AND INVITING.

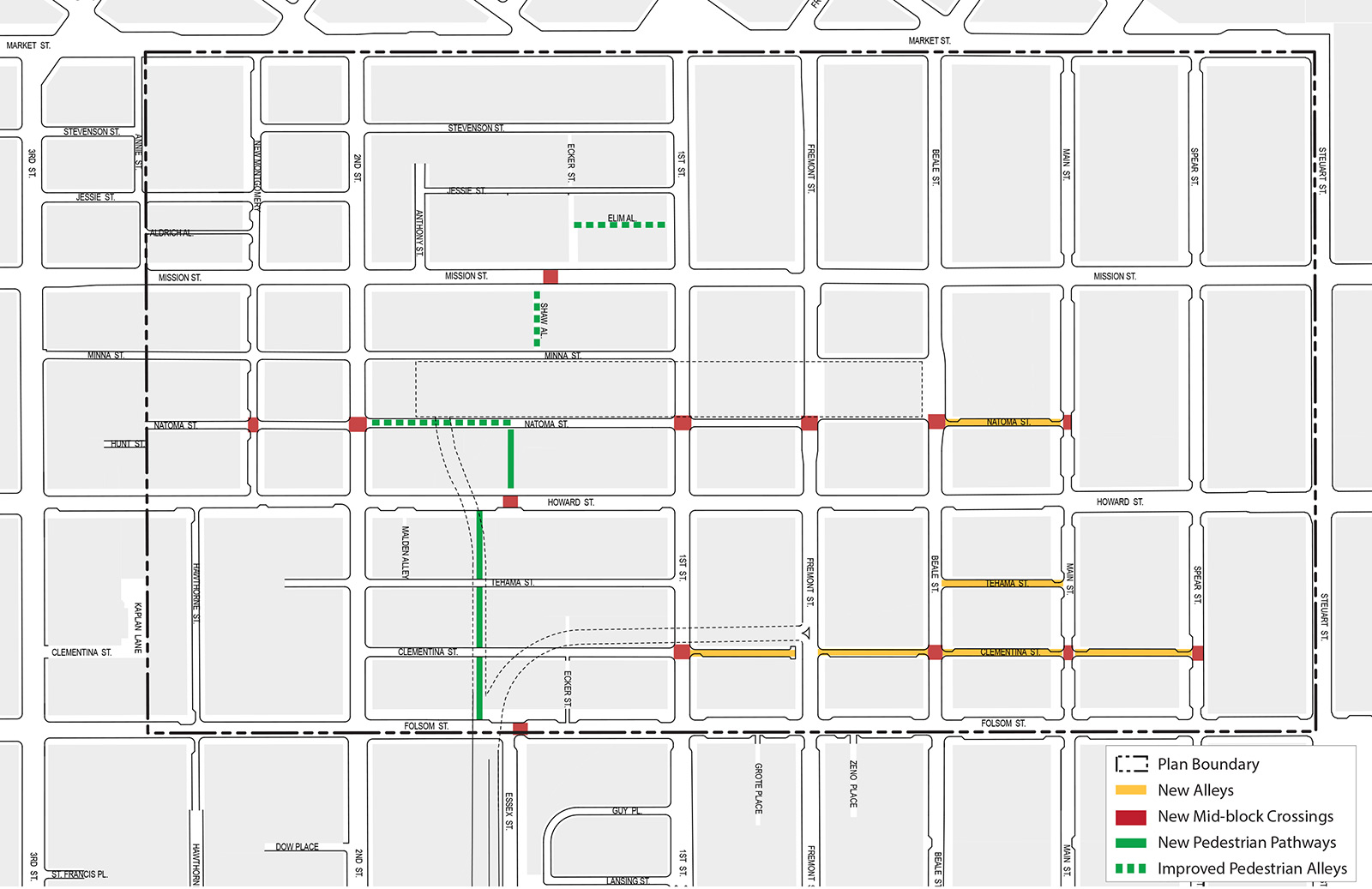

Many of the blocks in the Plan Area are very long, reducing the walkability of the district. The blocks between First and Second streets, in particular, are 850 feet long, necessitating a need for mid-block and through-block connections. The District’s alleyways are a character-defining element of the street fabric. They provide relief for pedestrian circulation, interest and diversity in the pedestrian network, and are critical for loading and parking access off of the main streets. Alleys additionally provide light and air in a dense district and create a more humane, fine scale of development. The Plan proposes to enhance this network by improving existing alleys, creating new mid-block pedestrian passages, as well as adding safe mid-block crossings. These improvements will help disperse pedestrians throughout the District, and allow access to the Transit Center at different points, thereby helping to relieve pedestrian congestion on key corners of major streets around the core of the district.

POLICY 3.10

Create convenient pedestrian access by providing signalized mid-block crosswalks, especially on blocks longer than 300 feet.

New pedestrian mid-block crossings should be introduced to ease access between major activity centers, as well as to help shorten pedestrian walking distances within the District. North-south pedestrian movement should be enhanced through the creation of three new mid-block crossings between 1st and 2nd Streets—on Mission Street near Shaw Alley, on Howard Street at mid-block, and Folsom Street at Essex Street. Several new crossings should be created along Natoma Street—at New Montgomery, Second, First, Fremont, Beale, and Main Streets—to facilitate access to the Transit Center and to emphasize its importance as an east-west pedestrian corridor. Lastly, the Transbay Redevelopment Plan proposes extending Clementina Street east to Spear Street. Mid-block crossings should be created where Clementina Street crosses First, Beale, Main, and Spear Streets to facilitate pedestrian access to the Transbay Park and to emphasize this new corridor.

POLICY 3.11

Prohibit the elimination of existing alleys within the District. Consider the benefits of shifting or re-configuring alley alignments if the proposal provides an equivalent or greater degree of public circulation.

Alleys are critical components of the pedestrian system and the character of the Plan area. Even the shortest and narrowest alleys, while seemingly insignificant in the present, will become ever more necessary as the district density intensifies and the population increases. The City’s General Plan (Urban Design Element Policies 2.8–2.10) acknowledges their importance and already generally prohibits the vacation of public rights-of-way except under unique and extraordinary circumstances in which the demonstrable public benefit of a proposed project requiring the vacation substantially outweighs the loss in public value (both current and potential) of maintaining the right-of-way in public ownership. However, based on other Plan policy and development goals for this District, it may be desirable to “shift” or build over certain narrow alleys for development purposes. In all of these cases, the General Plan explicitly requires the proposal of an actual development proposal for a public-right-of-way prior to consideration of vacation in order to weigh the specific merits of a particular development proposal against the loss of a public right-of-way.

POLICY 3.12

Design new and improved through-block pedestrian passages to make them attractive and functional parts of the public pedestrian network.

POLICY 3.13

Require a new public mid-block pedestrian pathway on Block 3721, connecting Howard and Natoma Streets between First and Second streets.