Environmental Justice Framework

DISCLAIMER: This Environmental Justice Framework articulates broad visions and priorities to guide city policy objectives. The Environmental Justice Framework does not identify specific future city policies and does not approve, fund, or authorize implementation of any specific projects. New and amended City policies and any implementation project will be reviewed and approved over time and follow protocols and best practices for adoption, which may require additional public review, review by City decision-makers, and/or environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act. As a result of those reviews, there may be alternatives and mitigation measures developed that may be implemented as well.

The Environmental Justice Framework also names example strategies and actions being performed in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community. Some of these examples are broad vision documents that guide City policies, and some are more concrete. Some have been adopted, and some are still under review at the time of this document’s writing. If and when any of the examples still under review is proposed for adoption, it will go through robust community planning and environmental review, as needed.

I. Introduction

"If we want a safe environment for our children and grandchildren, we must clean up our act, no matter how hard a task it might be.”

— Hazel M. Johnson, the “Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement”

“…Environmental justice is like an umbrella, and the spokes within the umbrella are made up of things like housing and economic justice, health, and education. If the spokes are broken, then the umbrella is inoperable.”

— Cheryl Johnson, daughter of Hazel M. Johnson

Every person deserves the opportunity to live in a healthy environment that supports their physical and mental well-being. In San Francisco, as in many other communities, we see that people of color, low-income residents, and other vulnerable1 groups are disproportionately exposed to hazards, such as unsafe housing conditions, illegal dumping, polluting industries, high-risk traffic conditions, crime, and violence. These communities often have limited access to supportive infrastructure and public services, such as healthy food, quality public education, stable and well-paying jobs, accessible parks, and other essential needs.

These injustices stem from a long history of environmental racism, a term that recognizes that American Indian, Black, Latinx, and other communities of color have historically borne—and in many cases, continue to bear—the brunt of environmental hazards due to systemically racist policies and actions. These racial disparities are compounded by the intersections with class, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, immigration status, and other identities that result in inequitable treatment or opportunities.

San Francisco’s history of state-sanctioned racism originated with the genocide, exploitation, and dispossession of the American Indian people on whose land our state and nation were founded. This history of racism extended through systems and policies that served to segregate, displace, and harm communities of color. The examples of state-sanctioned racism are too numerous to list in full, but include laws in the late 19th century limiting where people of Chinese descent could live and work; redlining practices and racial covenants starting in the 1930’s that excluded people of color from renting and buying homes in well-resourced neighborhoods; the forced removal and internment of people of Japanese descent during World War II; urban renewal projects and eminent domain during the 1950’s and 1960’s that were used to justify the wholesale displacement of Black residents and other communities of color; and the intentional siting of polluting freeways and industrial facilities in communities of color and low-income communities. Even though the City has taken steps to undo the damage caused by these past actions (for example, the formation of an African American Reparations Advisory Committee to develop recommendations for repairing harms in the Black community resulting from City policies), we continue to see pervasive health and other disparities along lines of race, place, and class. For instance, life expectancy in San Francisco greatly varies by race (72 years for Black residents vs. 82 years for white residents) and by neighborhood (77 years in the Bayview vs. 88 years in the Inner Sunset).2, 3, 4

The environmental justice movement grew largely out of the Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968), as communities afflicted by poor health outcomes fought for stronger environmental protections. These efforts gained prominence nationally, culminating in the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, followed by a federal government directive requiring agencies to address environmental justice in 1994.4, 5 The San Francisco Bay Area has a long legacy of community activism advancing economic, social, and environmental justice. San Franciscans have successfully fought for the closure of the last fossil fuel-fired power plant in the Bayview, the remediation and reconstruction of unsafe public housing facilities, funding for additional community facilities and infrastructure in EJ Communities, and stronger laws to mitigate pollution from new construction. Still, many environmental health challenges remain unresolved.

This Environmental Justice Framework (“EJ Framework”) acknowledges that local government has a critical role to play in working with communities to redress environmental injustices and move towards an equitable future. It leverages the City’s prior work to address environmental justice7 and identifies additional priorities for the City, based on collaboration with and feedback from community members. It is meant to guide decisionmakers and identify additional policy areas that will be incorporated throughout the San Francisco General Plan, in accordance with California Senate Bill 1000 (2016). The EJ Framework is also intended to align with the City’s work to advance racial and social equity, as directed by the Office of Racial Equity and resolutions by the Planning Commission and Historic Preservation Commission directing the Planning Department to center its work on racial and social equity.8, 9

The Planning for Healthy Communities Act (SB 1000)

California Senate Bill 1000 (SB 1000; “The Planning for Healthy Communities Act”) was authored by Senator Connie Leyva and co-sponsored by the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA) and the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ) in 2016. It requires cities and counties to either adopt an Environmental Justice Element or integrate policies, objectives, and goals to address environmental justice throughout other elements of their General Plan. These policies must reduce the “unique or compounded health risks” in the communities most impacted by environmental justice, spanning topics that include (but are not limited to) air quality, public facilities, food access, safe and sanitary homes, and physical activity.

1. In this context, “vulnerable” refers to groups that have reduced access to resources, including, but not limited to, youth, seniors, people with limited English proficiency, people with disabilities, and people returning from incarceration. It can also refer to groups that are more impacted by certain conditions, such as environmental injustices, housing displacement, health threats (e.g., asthma, COVID-19, etc.), and the impacts of the climate crisis.

2. City and County of San Francisco. Establishing African American Reparations Advisory Committee Ordinance (Ordinance No. 259-20). December 8, 2020.

3. San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership (SFHIP). San Francisco Community Health Needs Assessment 2019. 2019. Last accessed November 2022: http://www.sfhip.org/chna/sf-chna/

4. San Francisco Healthy Homes Project. Community Health Status Assessment. 2012. Last accessed November 2022: https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/EHSdocs/PHES/Healthy_Homes_Assessment_BVHP_2012.pdf

5. First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Principles of Environmental Justice. 1991. Last accessed November 2022: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.html

6. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of Executive Order 12898 – Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. 1994. Last accessed November 2022: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-executive-order-12898-federal-actions-address-environmental-justice

7. There have been numerous efforts throughout City agencies to address environmental justice. To name a few, the Department of Public Health, Department of the Environment, and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission have been leaders in developing policies and programs that reduce environmental pollution and advance healthy communities.

8. City and County of San Francisco. Racial Equity Ordinance (Ordinance No. 188-19). August 9, 2019.

9. San Francisco Planning Commission. Centering Planning on Racial and Social Equity (Resolution No. 20738). July 11, 2022.

II. What Is Environmental Justice?

In state and federal law, environmental justice is defined as the “fair treatment of people of all races, cultures, and incomes with respect to the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”10 For purposes of this EJ Framework, the City defines environmental justice as follows:11

Environmental Justice is the equitable distribution of environmental benefits and elimination of environmental burdens to promote healthy communities where everyone in San Francisco can thrive.

Government should foster environmental justice through processes that address, mitigate, and amend past injustices while enabling proactive, community-led solutions for the future.

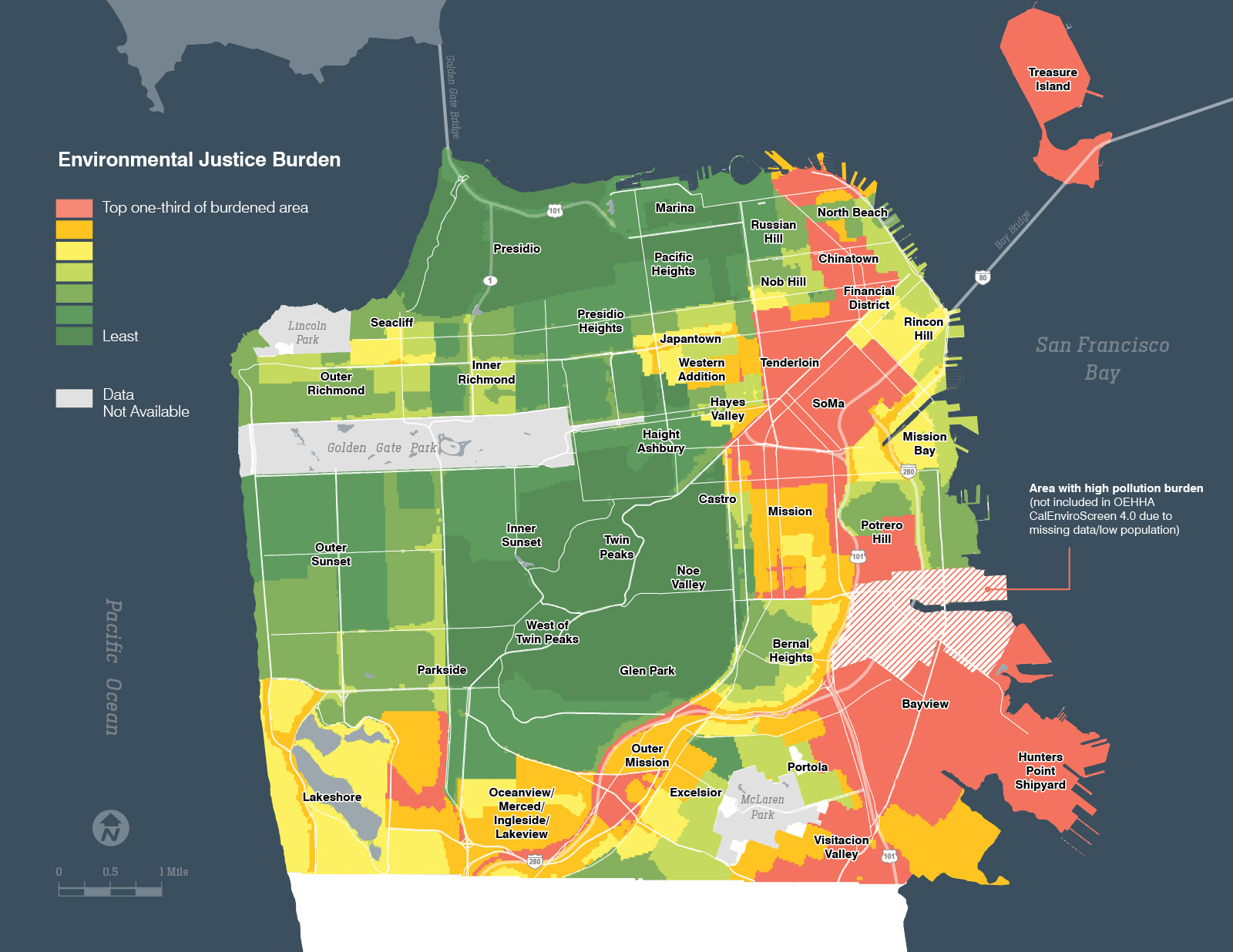

The EJ Framework has been guided by data analysis on environmental, economic, and health disparities, resulting in the development of an Environmental Justice Communities Map (“EJ Communities Map”; Figure 1). The EJ Communities Map depicts a gradient of pollution exposure and social vulnerability in San Francisco. It builds upon CalEnviroScreen, a map produced by the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA) and California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) and is refined with additional local data sources.12, 13 The areas in red are deemed Environmental Justice Communities, representing the top one-third of cumulative environmental hazards in the City. EJ Communities are often (though not exclusively) low-income communities and communities of color. These areas fall primarily along the southern and eastern areas of San Francisco and include neighborhoods such as Bayview Hunters Point, SoMa, Treasure Island, Mission, Tenderloin, Visitacion Valley, Chinatown, and Potrero Hill, among others.14

State guidance on SB 1000 calls for cities to convene a process for communities to become meaningfully involved in the decision-making processes governing land use planning in their neighborhoods. In this spirit, the EJ Framework has been developed in collaboration with community leaders, residents, and workers in the EJ Communities. The EJ Framework and EJ Communities Map received input and support through a range of engagement activities seeking to amplify the voices of community members—including a virtual open house, focus groups, youth engagement, and an Environmental Justice Working Group comprised of leaders from community-based organizations and City agencies. In particular, the Environmental Justice Working Group developed policy recommendations through a consensus-building process, which guided the development of the EJ Framework.15

What is the San Francisco Environmental Justice Framework?

This EJ Framework is part of Introduction to the San Francisco General Plan and provides guidance to City agencies on how they can address environmental justice in their work. It describes policy priorities to advance health in the Environmental Justice Communities—communities of color and lower-income communities that face higher pollution and other health risks—co-created with community members and organizations working in these areas. These priorities will be further developed into goals, objectives, and policies incorporated throughout the General Plan Elements. The first set of environmental justice policies are incorporated in the Safety and Resilience Element (adopted in 2022) and the Housing Element (adopted in 2023). Subsequent updates are planned for the Transportation Element (anticipated adoption in 2025) and other General Plan Amendments.

The San Francisco General Plan is a citywide document that enshrines the City’s vision for the future and guides our evolution and growth over time. Placing the EJ Framework within the Introduction serves to establish environmental justice and racial equity as foundational City goals that policymakers and City agencies should proactively address. Subsequent efforts should ensure that the EJ Communities are prioritized for specific policies and resources that can help redress historic injustices and meaningfully improve economic, health, and other outcomes.

FIGURE 1 - Environmental Justice Communities Map

Source: SF Planning, 2023

NOTE: This map was created to meet the requirements of CA Senate Bill 1000. The legislation requires that municipalities identify where "Disadvantaged Communities" are located, defined as areas facing elevated pollution burden coupled with a high incidence of low-income residents. This map is based on the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) CalEnviroScreen 4.0 Map, modified to incorporate additional local data on pollution burden and socioeconomic disadvantage.

10. California Code, Government Code § 65040.12, subd. (e).

11. This definition acknowledges the responsibility of government to partner with community to foster environmental justice, and it was informed by a literature review and feedback from community leaders. It also builds upon the decades-long efforts of environmental justice advocates (including the Environmental Justice Principles and the Jemez Principles of Democratic Organizing, which both grew out of the First People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991).

12. California Environmental Protection Agency and Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. California Communities Environmental Health Screening Tool (CalEnviroScreen). Last accessed November 2022: https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen/about-calenviroscreen

13. The San Francisco Environmental Justice Communities Map includes four main layers of data: CalEnviroScreen from CalEPA and OEHHA; state income limits from California Department of Housing and Community Development; Air Pollution Exposure Zone from San Francisco Department of Public Health; and Areas of Vulnerability analysis from SFDPH. The methodology follows the 2020 State General Plan Guidelines published by the California Office of Planning and Research, “Chapter 4: Required Elements.”

14. For more information on the San Francisco Environmental Justice Communities Map, see: https://sfplanning.org/project/environmental-justice-framework-and-general-plan-policies#ej-communities

15. Policy Recommendations for the Environmental Justice Framework. Environmental Justice Working Group. January 24, 2022. Last accessed January 2023: https://sfplanning.org/project/environmental-justice-framework-and-general-plan-policies#info

III. Environmental Justice Priorities

The EJ Framework outlines a set of visions and priorities across a range of policy topics critical to advancing environmental justice in the City. For each topic, the vision statement describes bold, aspirational outcomes that serve as a guidepost for implementation and enforcement. The priorities describe major activities the City can undertake to address environmental justice. Although many of these policy ideas could apply citywide, the EJ Framework is centered on priorities that people living and working in EJ Communities identified as critical to improving health in their neighborhoods. The EJ Framework guides all aspects of the General Plan, including the Elements, Area Plans, and Land Use Index.

The visions and priorities are organized in these six policy topics, adapted from SB 1000:

- Healthy and Resilient Environments

- Physical Activity and Healthy Public Facilities

- Healthy Food Access

- Safe, Healthy, and Affordable Homes

- Equitable and Green Jobs

- Empowered Neighborhoods

Healthy & Resilient Environments

WHY IT MATTERS

San Francisco has a long history of policy and land use decisions that have disproportionately exposed communities to environmental pollutants that impact quality of life and often result in adverse health outcomes, such as increased rates of asthma, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses. For example, residents in Bayview Hunter’s Point grapple with the impacts of industrial contamination at the Hunter’s Point Shipyard, air pollution from the U.S. Highway 101 and Interstate 280 freeways, and other environmental violations. The impacts of the climate crisis, which include poor and hazardous air quality, extreme weather events, and sea level rise, are predicted to exacerbate these health disparities.

VISION

We envision a City where everyone lives and works in a healthy and resilient environment. This means limiting exposure to pollution harmful to human health from both acute (e.g., toxic materials from an individual business) and widespread sources (e.g., air pollution from freeways). The City would be resilient to the climate crisis and other hazards, such as earthquakes, extreme heat, inland flooding, sea level rise, and poor air quality. Mitigation and adaptation strategies would prioritize communities that have historically faced disproportionate exposure to environmental burdens, and our most vulnerable communities at risk of health consequences and safety hazards, such as youth, seniors, and people with disabilities.

PRIORITIES

1.1. |

Protect communities from all sources of pollution, including air, soil, water, and noise pollution. Limit exposure from temporary sources of pollution (for example, construction activities), ongoing sources (for example, freeways and polluting businesses), as well as future risks (for example, accidental release of hazardous materials). |

|

1.2. |

Implement hazard and climate mitigation and adaptation measures to prepare the City for the climate crisis and protect those who are most vulnerable. Build robust partnerships between the City, communities, and other groups to ensure adequate capacity for emergency preparedness in the event of a disaster (for example, disaster supplies, lifeline supplies, and neighborhood activation). |

|

1.3. |

Restore natural habitats and the ecological function of the City by developing neighborhood-specific targets and stewardship programs for watersheds, tree canopy cover, green infrastructure, urban greening, and other biodiversity targets. Align these mitigation and adaptation measures to protect areas of high climate vulnerability. |

|

1.4. |

Ensure that all residents and workers have access to safe, clean, affordable, accessible, and low-carbon sources of clean drinking water, electricity, wastewater services, broadband internet, and other utilities. Invest resources and promote actions that support the human right to water, power, and sanitation, particularly low-income households and people experiencing homelessness. |

|

1.5. |

Provide public access to reliable and up-to-date information on neighborhood environmental conditions, climate vulnerabilities, and public health concerns. Include references to government sources and community-led studies and programs. |

|

1.6. |

Build community-based planning processes for San Franciscans to engage in local decision-making on healthy and resilient environments, including neighborhood investments, emergency resources, and other community needs. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

CleanPowerSF (SFPUC)

-

Hazards and Climate Resilience Plan (ORCP)

-

Heat and Air Quality Resilience Project (ORCP)

-

Islais Creek Southeast Mobility and Adaptation Strategy (SF Planning, SFMTA, and Port of San Francisco)

-

San Francisco Climate Action Plan (Mayor’s Office, SF Environment)

-

San Francisco Urban Forest Plan (Public Works, Urban Forest Council, and Friends of the Urban Forest)

-

Urban Risk Lab (Neighborhood Empowerment Network)

-

Waterfront Resilience Program (Port of San Francisco)

Physical Activity & Healthy Public Facilities

WHY IT MATTERS

The health benefits of daily physical activity are well-documented. Throughout the public engagement process, EJ Communities expressed the need for improved access to parks, recreation centers, and other community facilities; programming that better suits the needs of their families and communities; and other opportunities to engage in daily physical activity. Similarly, residents and workers described barriers to traveling on city streets by foot, bike, and transit, with a high number of fatalities and severe injuries concentrated on streets in EJ Communities. This further limits people’s ability to get around safely and discourages many from incorporating physical activity into their daily routine.

VISION

We envision a City where everyone can access healthy public facilities and engage in regular physical activity. This means that public facilities—such as community centers, libraries, parks and recreation facilities, schools, and hospitals—are situated, designed, staffed, and programmed to ensure equitable access and safety for all. These public facilities and the transportation network that connects them to the community should facilitate active and low-carbon transportation modes, such as walking, cycling, and public transit. Regular physical activity is critical for physical and mental well-being, helping reduce stress, anxiety, and depression and helping prevent certain chronic health conditions.

PRIORITIES

2.1. |

Evaluate the need for community facilities in EJ Communities and add new or expand existing facilities as needed. |

|

2.2. |

Ensure that all public facilities are safe, clean, and inviting and offer safe and convenient access for people of all ages, abilities, and identities, including individuals and families experiencing homelessness. |

|

2.3. |

Expand program offerings at public facilities to meet dynamic and evolving community needs. Partner with the community to ensure that programming is culturally appropriate and inclusive. Offer a range of opportunities for people of all ages, abilities, and cultures to participate in public programs. |

|

2.4. |

Expand programs providing opportunities to engage with the natural world, such as community gardens, nature walks, environmental education, and other environmental programming offered in parks and public open spaces. |

|

2.5. |

Protect, maintain, and invest in transportation infrastructure and services that offer accessible, interconnected, and affordable mobility options, including streets, sidewalks, active transportation, and transit. Improve transportation network connectivity where gaps exist due to freeways, rail lines, and other transportation infrastructure (such as at underpasses and overpasses). |

|

2.6. |

Ensure that streets and transit are accessible, safe, convenient, and supportive of active transportation modes such as walking and cycling. Prioritize investments in communities that have experienced disconnection and disinvestment from past transportation planning. Prioritize street improvements aligned with the City’s Vision Zero Strategy, which aims to eliminate traffic fatalities. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

Equity Zones (SF Recreation and Parks)

-

Green Infrastructure Grant program (SFPUC)

-

Green Schoolyards Program (San Francisco Unified School District)

-

Muni Service Equity Strategy (SFMTA)

-

Safe Routes to School (SFMTA)

-

San Francisco Green Connections (multiple City agencies)

-

Southeast Community Center (SFPUC)

-

Vision Zero SF (SFMTA)

Healthy Food Access

WHY IT MATTERS

One in four San Francisco residents is at high risk of food insecurity due to low income, and there are significant disparities in accessing healthy food that is affordable and culturally appropriate. Being food insecure is associated with lowered life expectancy and a range of chronic health conditions, it and can be especially harmful to the health of children and seniors, people who are pregnant, people experiencing homelessness, and people with preexisting health conditions.

VISION

We envision a City where everyone has easy and secure access to healthy, affordable food that suits their needs and dietary preferences, and supports their cultural identity. Food is healthy when it promotes a healthy environment and the well-being of everyone involved in its production, processing, distribution, consumption, and disposal.

PRIORITIES

3.1. |

Expand programs that ensure access to healthy and culturally appropriate food, particularly for fixed income, low-income, and food-insecure individuals, such as Market Match programs, free school meals, healthy corner stores, food recovery, and urban agriculture programs. |

|

3.2. |

Consult with workers and community members to create local food assistance programs, workforce development programs, and other programs that facilitate access to healthy food and create living-wage jobs. |

|

3.3. |

Consider the potential benefits of a local food system for workforce development, economic resilience, sustainable land use, and improved public health outcomes in City plans and programs. |

|

3.4. |

Facilitate local and regional food production (such as community gardens, rooftop and vertical gardens, and cottage industries), incorporate climate resilience throughout the local supply chain (such as net-zero emissions food distribution and infrastructure investments), and support youth training and workforce development in healthy food-related skills and industries. |

|

3.5. |

Affirm Traditional Ecological Knowledge16 and nature-based food practices. Support nature-based and culturally appropriate access to public land and open space for foraging, gathering, cultivating, fishing, and hunting17 of food as well as conducting other nature-based cultural practices. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

Urban Agriculture Program (SF Recreation and Parks)

-

Free and Reduced School Meals Program (San Francisco Unified School District)

-

Food Recovery Program (The SF Market)

Safe, Healthy, & Affordable Homes

WHY IT MATTERS

Access to safe, healthy, and affordable homes is a basic human right, and it is integral to one’s health and economic security. The soaring cost of housing in San Francisco has further magnified racial and social disparities and has led to the decline in population of people of color (specifically American Indian, Black, and Japanese residents) and to the increase in the number of unhoused and housing-insecure individuals. Additionally, many vulnerable low-income and people of color residents find themselves living in increasingly unhealthy and precarious living conditions (e.g., poor indoor air quality, overcrowding, lack of heating or clean water). The trauma of housing displacement and housing insecurity impacts health, education, and employment outcomes that can affect people throughout their lives, as well as that of future generations.

VISION

Every person in San Francisco has the right to a safe, healthy, and affordable home, regardless of race or ethnicity, national origin, immigration status, disability, sexual orientation, or language spoken. Residents should be free to live in peace without worry of unsafe living conditions, harassment, or threat of eviction by landlords. Healthy homes should be built using non-toxic building materials and have easy access to public facilities, parks, public transportation, and healthy food options.

PRIORITIES

4.1. |

Work to repair past injustices and stop or reverse the population decline of American Indian, Black, Japanese, other people of color, and other communities that have experienced displacement. |

|

4.2. |

Increase accountability and public participation in the development and implementation of housing programs, particularly for groups representing American Indian, Black, other people of color, and other disadvantaged communities. |

|

4.3. |

Increase funding for affordable housing development, stabilization, and site acquisition at the scale needed to ensure full affordability for all those whose incomes prevent them from accessing stable housing. Explore models such as community land trusts, affordable ADUs, affordable homeownership, and other ways for low- and moderate-income residents to build equity through housing. |

|

4.4. |

Prioritize support for vulnerable renters, including expanded access to affordable rental and ownership units, culturally competent housing outreach and education programs, and protections against involuntary displacement. |

|

4.5. |

Expand affordable housing in San Francisco’s higher income neighborhoods, such as the western and northern areas of the City, enabling more residents to benefit from greater access to public and active transportation, educational opportunities, community facilities, retail, and other services. |

|

4.6. |

Ensure that existing and new developments include features that contribute to physical and mental health, such as open spaces, communal areas, and recreation amenities. Work to, stabilize, preserve, and upgrade existing housing stock to address unhealthy living conditions. Eliminate the use of toxic materials and ensure that housing built on environmentally contaminated land undergoes strict procedures for remediation, community engagement, and reporting. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

Child Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (SFDPH)

-

Advocacy for increased local, regional, state, and federal funding for affordable housing

-

Acquisition and rehabilitation programs to stabilize tenants in existing affordable housing (such as MOHCD’s Small Sites program)

-

Increased funding and enforcement to protect vulnerable tenants from the threat of displacement

-

Programs targeting residents displaced by urban renewal and their descendants (such as Certificates of Preference)

Equitable & Green Jobs

WHY IT MATTERS

As it becomes increasingly expensive to live in San Francisco, there is a growing need to ensure that the City offers a diversity of jobs that provide living wages and opportunities for workforce training, and career growth. San Francisco has the second highest income inequality in the Bay Area, with significant disparities in income and workforce participation.18 There is significant opportunity to remedy the underrepresentation of Environmental Justice Communities in well-paying vocations and careers. To address income disparities and unemployment rates, the City can support and advance policies that ensure living wages, offer quality benefits (e.g., sick leave, health care, retirement), promote dignified labor, expand career advancement opportunities, and generate social and economic benefits to the community.

VISION

We envision a City with an abundant network of jobs and workforce opportunities that contribute to the development of healthy communities. All jobs in San Francisco would provide living wages and benefits, value workers’ physical and mental health, and offer workforce training and professional development opportunities. This network of jobs and workforce opportunities would include, but is not limited to, established and emerging industries contributing to public health and environmental sustainability such as healthcare, renewable energy, environmental remediation, and other related fields.

PRIORITIES

5.1. |

Ensure that low-income people and people of color communities have access to jobs that pay a living wage and provide workforce training and professional advancement opportunities. |

|

5.2. |

Dedicate City resources to building jobs and workforce opportunities, providing training and mentorship, and advancing emerging trades and industries that contribute to healthy communities. Offer tools, resources, and networks that provide workforce training, apprenticeships, mentorship, career development, management opportunities, and facilitate business ownership. |

|

5.3. |

Create employment pathways along the jobs pipeline that enable youth, seniors, returning citizens,19 and other underrepresented groups to participate in equitable and green jobs of their choosing. Protect and strengthen organized labor and other types of business ownership, such as worker-owned cooperatives. |

|

5.4. |

Incorporate environmental justice as a pillar of the City’s economic future, particularly through local and small business development. A fair and just transition20 would ensure the City’s job opportunities and economy prioritize and uphold sustainability principles, as well as secure workers’ rights and contribute to their health. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

CityBuild (OEWD)

-

CityDrive Program (OEWD)

-

Gardener Apprentice Program (SF Recreation and Parks)

-

Green Construction Training (Success Centers)

-

Greenager Program (SF Recreation and Parks)

-

HealthCare Academy (OEWD)

-

Kitchen Incubator Program (La Cocina)

-

Local Business Enterprise Ordinance (CMD)

-

Youth Stewardship Program (SF Recreation and Parks)

-

Apprenticeship programs in cement masonry, horticulture, and environmental services (Public Works)

-

Construction pre-apprenticeship training program in Tuolumne County (SFPUC)

-

Work-based learning opportunities for SFUSD students (SFPUC)

Empowered Neighborhoods

WHY IT MATTERS

Despite San Francisco’s longstanding legacy as an incubator of community-led activism and its rich tapestry of civic organizations, the City continues to receive feedback that people feel unheard, particularly when it comes to decisions that impact historically under-resourced communities. The City’s complex public decision-making processes can make it difficult and time-consuming for many people to participate in processes that stand to directly impact them. Even when people can participate, there is often deep-seated skepticism about whether their feedback will be incorporated.

VISION

We envision San Francisco residents, business owners, and community organizations working across neighborhood boundaries and collaborating with elected officials and City departments to inform and impact decision-making processes. Empowered neighborhoods prioritize community cohesion, hold their City officials accountable, and are provided with resources to enable change within their communities. Empowered neighborhoods move beyond transactional relationships with City government by working together to both undo the harms of past actions and also actively define and facilitate equitable and just outcomes.

PRIORITIES

6.1. |

Seek and devote resources to engaging meaningful, ongoing participation and community involvement in decisions that are most likely to impact EJ Communities. |

|

6.2. |

Establish orientation materials, trainings, and capacity-building opportunities for community members to fully participate in decision-making processes. Ensure these opportunities prioritize communities that have been historically excluded from and disenfranchised by policymaking processes, particularly American Indian, Black, Latinx, other communities of color, and other vulnerable groups. Increase participation accessibility for those who may experience barriers to participation (such as youth, seniors, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+, transgender, transitional-aged youth, etc.) Establish fair and accountable processes to compensate community members for their time and effort. |

|

6.3. |

As First Peoples, American Indians have an inherent relationship with the land as traditional stewards, and a unique understanding of natural environments that predates modern science. Future initiatives should include intensive collaboration with American Indian tribes throughout the scoping, development, adoption, and implementation processes. |

|

6.4. |

Develop a culture of transparency through proactive and accessible public notice, communication, and engagement from the City regarding projects that would impact EJ Communities. |

|

6.5. |

Support opportunities for peer knowledge-sharing and collaborative partnerships between communities and the City. Partner with the San Francisco Cultural Districts and other community institutions to expand outreach and communication between the City and EJ Communities. |

|

6.6. |

Work collaboratively with communities to address public safety, as it is a public health challenge and major impediment to community cohesion and participation. |

EXAMPLE STRATEGIES

The following strategies are examples of successful work being done in the community related to environmental justice. They include City-led initiatives, community-led initiatives, and partnerships between the City and community.

-

Environmental Justice Grant Program (SF Environment)

-

Racial & Social Equity Action Plans (all City departments)

-

San Francisco African American Reparations Advisory Committee (SF Human Rights Commission)

-

San Francisco Cultural Districts Program

-

Community Advisory Committees and other advisory groups

16. According to the National Park Service, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is “…the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.” (Source: National Park Service (2020). "Overview of TEK.” Accessed January 5, 2023 at: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm)

17. There are currently no designated areas within the boundaries of the City and County of San Francisco for hunting. However, this policy priority reflects feedback from the American Indian community to have opportunities for practicing their food cultures. This policy priority supports regional opportunities for hunting.

18. San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership (SFHIP). Community Health Data. Economic Environment. 2022. Last accessed January 2023: http://www.sfhip.org/chna/community-health-data/economic-environment/

19. The term “returning citizens” is an alternative to more stigmatized terms for individuals returning home after being in incarceration (e.g., ex-con, ex-felon). For more, see: https://unitedreturningcitizens.org/what-is-a-returning-citizen/

20. “Just Transition is a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy. This means approaching production and consumption cycles holistically and waste-free. The transition itself must be just and equitable; redressing past harms and creating new relationships of power for the future through reparations.” – Climate Justice Alliance. For more, see: https:///climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition

21. According to the National Park Service, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is “…the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.” (Source: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm)

The Environmental Justice Framework was adopted by the Board of Supervisors Ordinance No. 0084-23 on 05/09/2023.